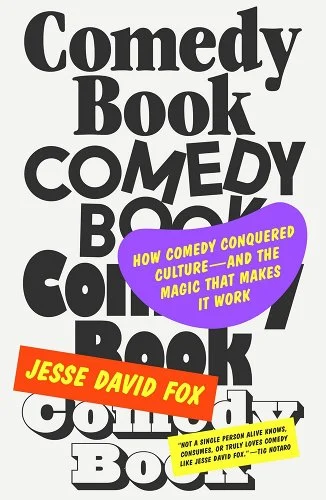

Jesse David Fox wrote the book on comedy (Photo by Mindy Tucker, illustration by Johansen Peralta)

A new book gets serious about comedy

'Comedy Book' by Vulture writer Jesse David Fox makes a compelling case for comedy as a form of art

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

If you like comedy, have we got a book for you. It’s called “Comedy Book” and it’s by Jesse David Fox.

The full title is “Comedy Book: How Comedy Conquered Culture, and the Magic That Makes It Work.” And it is at its heart an argument that comedy is an art form — and as an art form, it should be treated just as seriously as any other art form out there. It is also an explicit love letter to comedy: first and foremost, live stand-up comedy, but also sketch comedy, improv, comedy specials, and episodic shows with a comedy accent. It is also a history of the modern era of comedy of the past 30 years or so and a philosophical probe into what this comedy thing is anyway.

If you like stuff that has made you laugh on purpose or care about the context in which it got made, you might want to read this book.

“I wrote this book for audiences, I didn’t write this book for comedians, says Fox, who is this week’s guest on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast.” “I want a better informed audience or more passionate audience because I think it results in better comedy.”

Fox, who is a senior editor at Vulture, where he covers comedy, talks about about truth and comedy, community and comedy, context and comedy, flashpoints in the comedy scene, Louis C.K., Hassan Minhaj, Bowen Yang and Las Culturistas. We talk about Matt Rife, the algorithm and more.

I can promise you it’s interesting, I can’t promise you that we’ll be as funny as professionally trained comedians, but hang in there.

The following is a transcript of our conversation, which airs as an episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast,” edited for clarity. Listen in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

I’ve enjoyed reading your book. I’m a comedy nerd that’s maybe behind the times a little bit. I’m not as up to speed as you are, I would say.

It demands a lot to keep track of, especially now because everything’s so spread out, you’d have to essentially have algorithms send you stuff you don’t even like just because you want to know what’s out there. And that’s a lot to ask a regular person.

For sure. And we’ll get to the algorithms in a bit, but I wanted to ask you first, what was the last live show you saw?

Every other Tuesday at Union Hall Vulture co-presents a show called Pretty Major.

Oh, you’re still doing that?

If anything, it’s really feel like it’s found its footing in the last few months where every one, it’s a really good lineup, people really coming out, the audiences are really good. So that was, I don’t know, a week ago or two weeks ago, and it was really, really good. I’m trying to think, I can’t even remember who’s on the lineup, but it’s hosted by Jay Jurdan and Zach Zimmerman and they’re there every week.

For 20 years now Union Hall has been a really incredible comedy hub.

It’s my favorite comedy venue. When I first moved to Brooklyn, I moved nearby, so I’ve been going to Union Hall for 15, 16 years.

We’ve never met before this, but I’m sure we’ve sat in the same room at least once or twice because there’s an interesting cluster of places. In Gowanus, there’s Littlefield, and The Bell House has pivoted more in comedy than music in recent years.

I just moved to Brooklyn and because I lived nearby, I emailed Union Hall and I go, “Hey, can I take photos at shows? Not professionally, just like, is that allowed?” I was so young, I just didn’t know. I had a camera and they’re like, “Yeah, I guess.” And then a year later they emailed me and they were like, “Do you still want to take photos at shows? You can come to any show you want, if you’ll take photos here or at The Bell House and we’ll give you bar tabs,” or something like that. So then I was like an in-house photographer for the two venues.

But the thing is I would go to, who knows, one or two shows a week, I would take photos, send it to some email, and then I have no idea what they ever did with those photos. I wasn’t even a professional photographer, I was just a person who asked. The thing that I had since learned is, the whole reason it really became a comedy venue, it was Eugene Mirman moved nearby so he put his show there and once a thing becomes a thing, then people are like, “Oh, can I do my show there?” And then those shows sell more consistently than sort of odds-or-ends concerts, and then next thing you know, to me, the best comedy venue in the country.

We’ve had him on the podcast because he came back and did his reunion show at the Bell House and he was great.

The first show I ever saw at Union Hall was him watching his Comedy Central Hour. We’re all watching the special on TV at the Union Hall sold out, and then he was just on the side laughing. It was so funny. I’ve never seen a comedian laugh at his own jokes

This book is almost like a conversation starter in a way. It’s not the definitive history so much as, in your words, an exploration of the ways of seeing the art of comedy. “Comedy” in this case is stand-up, sketch, internet, comedy shows, blah, blah, blah. It feels less of a final word than an elaborate opening salvo.

Yeah, I think that’s exactly correct. I could not write a definitive history because I think I was focused on modern comedy and by the time I’m writing about it, monoculture was fading away enough that it’s hard to say what is definitive, it’d just be my perspective, and I don’t think my perspective is definitive. And through my years of doing it, especially through interviews, but through research, you just would find tropes and cliches said about comedy. Opinions. The most famous is “you can’t analyze jokes,” but things about comedians are modern day philosophers, comedians are modern day truth tellers, these ideas around truth and comedy.

“Comedy is tragedy plus time.”

“Comedians must cross the line deliberately,” whatever, all those things. I found all of them wrongheaded and/or naive and/or limiting. And I was curious where they came from and I wanted to upend almost all of them. I think my goal, especially after when I worked on the proposal, which included a lot of what is in the first chapter, which is about how we think of jokes incorrectly. Comedy is in art form, and when we associate it with just jokes, it becomes too easy to conflate it with joke-book type jokes, and these are different things. The goal is at least once a chapter say something that is provocative to upend one of the existing theories of what comedy is. Like chapter two I talk about how comedy booms don’t exist. That is a misnomer.

“Booms” meaning the received wisdom is that you had the guy in front of a brick wall in the ’80s speaking his truth, and then the alt comedy scene in the ’90s and then blah, blah, blah.

I don’t want to change people’s opinions, I want to change how they form their opinions. That is also ambitious. It took me a few years, but I would rank best stand-up specials of the year when I was at Vulture for a while, and then I got really in my head about the fact that I watch 150 stand-up specials a year, whatever it is, and most people watch three, two. I’m like an advanced being trying to communicate with primitive life forms. It felt like it had a completely different vocabulary. I understand that is what a critic is supposed to do, but it got really in my head about what exactly am I communicating when I say something is good or better? So my focus was sort of on these value systems and how do we form these value systems? And then when I had that vocabulary, I would look at like, “Well, what is valued in comedy? Why is it valued? How can I not change what people think is good, but change how they come to what they value?”

I really like the way you approach the notion of what is funny. You have a very expansive and generous view of comedy. There’s room for poop jokes, there’s room for Adam Sandler at his most “Jack and Jill,” lowest common denominator, as well as room for the Hannah Gatsbys and Bo Burnhams of the world, a little more cerebral. Essentially, if something is funny to someone, it’s funny, which is the anti-gatekeeper approach, I guess.

That’s the goal. I think I can appreciate more types of comedy than most people can just because most people, they either find something funny or not, and if they don’t, they’re like, “Well, this is probably bad.” You’re like, “Well, no, people like it.” And maybe like when you go to an art museum, you could look at a painting and be like, “This doesn’t respond to me, but it is interesting that it exists in this room.” Can you have that approach when you’re at a live comedy show and you’re seeing nine comedians?

And I’m aware that I’m different or I go to a comedy show and I’m there as much for the audience as I’m there for the acts. One of the ideas that I push back on is a thing that a comedian like Jerry Seinfeld will say, which is, “funny is funny.” And what he means is it’s undeniable, if you’re funny to me, you’re funny. What that ignores is there’s things that he doesn’t find funny that other people find funny that are probably also funny. So I try to explain to people that, as impossible as it seems, everything that a comedian probably is doing, by the time you see it, people find it funny. So you can’t really write the problem with it is it’s not funny. That’s actually not telling us anything.

Yeah. That’s not helpful.

I understand in some ways what a critic is saying is, “I don’t find it funny and you reading me, you associate yourself with me and we have similar tastes, so then you should also not find it funny.” But I think it’s actually more useful to be like, “Oh, the problem with it is not that it’s not funny, it’s that it gets it at a way that is easy or done before, and I find that boring. However, if you are a child, you probably have not seen this before and you’ll like it.” That’s ultimately a lot of it. A lot of sort of “lowbrow” comedy or easy comedy appeals to kids because they haven’t seen it before and that’s great. What, do you not want them to have that? If you don’t have poop jokes when you’re a kid, then you’re never going to get them.

Well, fortunately they never go out of style.

No, they’re eternal. There’s nothing inherently funny about anything other than that. It is so human, and I believe the great comedy comes from the human experience.

The “funny is funny” [theory] breaks down when the comedy speaks to an experience that Jerry Seinfeld has never had, whether it’s being a marginalized person or an experience as an outsider in a way that he has not experienced. So it brings in the idea of community in comedy, which can cut both ways. You have bell hooks cutting it up with Cornel West in your book showing the power of comedy as binding marginalized communities. You see that with Las Culturistas. But communities also use comedy to keep people out.

Chapter 10 is about community. And when I started writing the book, “community” was a word that was being thrown around a lot and it’s like, “That’s going to save us.” There’s just so many people like, “What we need more is more community,” and blah, blah, blah. And then you spend enough time researching community as a concept and you realize it’s not inherently a good thing. I think community is a good thing to the individuals in said community no matter what, it biggens their soul or something like that. But it’s not always a societally good thing.

Yeah, the community itself could be a bad community or a bad actor.

Yeah. So that community might be antisocial and it’s ultimately like its mission. How comedy interacts with this is that comedy, because the idea of getting a joke is so part of you that if you get the joke, you’re part of an in-group. But if you don’t get the joke, you are an out-group and communities need out-groups to help form themselves. Now, people’s relationship to the out-group can be different. In many ways, even the most accepting communities are hostile to the out-group, which is people who are maybe bigoted, but there’s still a hostility of the people in the out-group.

I wanted to explain that, one, comedy’s ability to smooth tensions between disparate people and create a large in-group that is maybe made up a dissimilar people, but with similar objectives that are pro-social is one of the best things it can do that. It’s in that politics chapter and I talk about people are always like, “What can comedy do to save the republic?” Or something, and they want it to change people’s minds. And I’m like, “Actually, the thing that can do is ease tensions and bring people together and that unit could help move us.”

Spark empathy?

But at the same time, comedy still clearly creates out groups. Certain group of comedians make jokes about groups of people, and that group changes based on who’s in the news. Ten years ago it was all about gay people because gay marriage was the main issue, now a lot of the jokes are about trans people. So what these comedians who want to do that do is they make fun of that group and they create an in-group that is hostile to them or just is fine making fun of them. And it’s the same like, “Well, we’re an in-group that doesn’t include those people, or if those people want to be part of this in-group they have to do the work of accepting being joked about, and that’s the price they pay is getting it.”

And the problem is this sort of what, I guess you can call an “anti-social community” in terms of comedy, is even if those people are not trying to be bigoted, they’re like, “Look, we’re all in this together, we’re equal opportunity offenders. We can joke about anything. You come here, we’ll joke about this group, but you can joke about us, we’ll joke about them and it’s all equal.” Though that is an idealistic idea that I could see everyone’s brain could aspire to that. If everyone was equal and we all made fun of each other equally, sure, that does seem fine. That’s like what it’s like to be with your friends.

Well, there are power imbalances, right?

Yeah, there’s power imbalances, but also the work of the community is not only kept in the community, people can then use it and use it for sort of more bigoted ends. And the thing about the jokes about groups, jokes that transgress on certain things like vaccine mandates or whatever, is that bad actors have realized that they can essentially bastardize that and use that to normalize bigoted opinions.

This is on the record in the book, I have a quote, which is they’re like, “Oh, we can use these sort of soft jokes where we ironically joke about the Holocaust to then normalize that type of speech and then use the sort of YouTube algorithm or Instagram algorithm or TikTok algorithm that likes to push you to more and more and extreme of content to trick a young person who might not know the difference, who didn’t go into this to be anti-Semitic, to trick them into finding actually intentionally anti-Semitic comedy funny.” And next thing you know, they wouldn’t say they’re anti-Semitic, but their favorite comedian is actually Nick Fuentes or whatever, who’s not a comedian, but just a Nazi.

Yeah, radicalize them. In a lot of respects, this book is as much a history of the evolution of media over the last 30 years as it is about comedy itself. Then you get into the idea of contextless comedy, the fact that we all have infinite laughs right here on our phone at the touch of a finger — minus the community, minus being in the room where it happens. And that lack of situational context can either be benign or it can be used to radicalize or disseminate hate.

Comedy is so quick to adapt to new technologies — because comedy is so cheap to produce and this has historically been the case — this is not just through social media, this has been the case since records. The first records made, a lot of them are little comedy skits because comedians don’t need anything else, they can just show up and they could talk. So records, television, there was a lot of stand-ups in early television, film, whatever. And part of the reason comedy is so big now is there’s been so many technologies that comedians have been first to market on, podcasts, YouTube, Instagram, Reel, TikTok.

Comedy and porn are the two.

Honestly, it’s a good way of putting it, right? I wish I had that point. So as a result to talk about comedy over the last 30, 40 years is to talk about media and how comedy’s reacted to media. And so when you study audiences, as I do, you start realizing the shorthand that comedians might use with their audience. So I’m familiar with this comedian who exists in this sphere with their fans, and I know what they mean when they do this, but then I see what happens when it’s moved over to a different space and people are like, “This isn’t funny at all.” And it’s like, well, it’s just like when you’re with your group of friends, you have inside jokes. If you then started doing those inside jokes with a complete group of strangers, they would think you’re really weird and not funny. They’d just be like, “What are you saying?”

And it’s usually a benign thing that happens, which is like, “Oh, I don’t find this person funny,” but what happens is over and over again, we’re seeing these things bump into each other where comedy that should be existing in a certain bubble is reaching other people. Without the context, it’s hard to even conceive of it as comedy as all. As I say, most comedy is really person-based. It’s not just saying a funny thing, it’s like who that person is and what they’re doing. If you think of a sitcom, it is the situation. It’s not just the things they say. So it’s like if someone was wearing a mask and had a knife, you’d be scared no matter what, where if you saw someone in the street in a wedding dress, you would not be like, “Oh, that’s the funniest thing I’ve ever seen.” You’d be like, “Oh, something’s wrong with this person.” But in the context of comedy, you understand that it’s comedy.

That was a “Bridesmaids” reference for everyone who hasn’t seen the movie.

In my head everyone has seen it. Literally that is one of the few things where I’m like, “Well, everyone has seen that movie or at least knows that scene that’s in the trailer.” So comedy needs context to operate. There’s sort of no version without it, but it becomes really complicated because the internet removes context and you are constantly bumping into things that doesn’t make sense to you when things don’t make sense to you or a lot of people’s reactions, especially because of how social media works, is to sort of negatively react to it. And that becomes really complicated with irony.

I don’t know what you do. I literally don’t know how irony can exist anymore on the internet, and that’s why I try to be like, “Please go to live shows,” where everyone understands it when people are being ironic. But when you’re on the internet, you see people doing the most softly ironic joke about race or gender or politics broadly, they might make a joke about voting for Trump, let’s say, the most basic thing, but you remove the context of who they are or tone and you start seeing people say things like, “Yeah, I know they’re joking, but I don’t believe it.”

And that shouldn’t happen, but that’s because we’re moving the sort of basic thing of how comedy needs to operate, which is sort of like we’re all in the same space and the comedian is feeling out the norms of that space, where Twitter or whatever it’s called now, or Instagram, there are no norms of that space mixed with people who are actively trying to remove the ironic frame on certain things to act like certain comedians are actually trying to have different political opinions than they have.

Actual disinformation, right?

The thing that has to happen is, and this is where it’s really hard, is comedians have to decide how they feel about if the audience gets their jokes incorrectly and how do they feel about it?

It’s almost Andy Kaufman-esque, right, to play in that space and not care about the context or what the audience thinks or deliberately poke the bear a little bit?

There’s a lot to do there. The problem is there’s so much tension there because people really are confusedly going here. So it becomes so easy to trick people, you really have to understand why you’re trying to trick people because it really is so easy to trick people. I wrote about Brad Evans and Nick Ciarelli who did the “Moves like Bloomberg” thing.

Which was a spoof on a Buttigieg video, right?

So essentially they did a fake campaign video for Bloomberg. Their goal was to make fun of a Buttigieg video to their followers or whatever, and they were aware that maybe it would get picked up, and the idea of people get Onion headlines wrong, but they didn’t expect what happened: Major members of the Republican Party used their videos an opportunity to make fun of the state of the Democratic Party or something. Now, what that does is effectively communicate whatever satirical point they were making about the nature of political media.

Look out #TeamPete because us Bloomberg Heads have our own dance! Taken at the Mike Bloomberg rally in Beverly Hills. #Bloomberg2020 #MovesLikeBloomberg pic.twitter.com/UCNo0fRZcE

— nick ciarelli (@nickciarelli) December 13, 2019

But if that point is lost on the Republicans who retweeted it and their followers … ?

Then I don’t know, who knows? Now that video exists, someone can intentionally completely clip it, remove it even further from the context and then use it further. It’s a really complicated time to exist and the things that a comedian can do, ultimately, if you’re worried about this, there are obviously so much things you can do to play with this. But if you’re a comedian who’s worried about it, you just have to put a lot of visual information, you have to communicate a lot of information into your work to be like, “This is the space that it is, this is the rules of it,” which is always what comedians have to do. But I think a lot of comedians film their specials live, so they’re like, “That’s all the context I need.” Well, it’s like, no, if you have your special watched on Netflix, the algorithm is telling people what to watch, they don’t know who you are.

What you’re saying though brings me to the idea of truth in comedy, which is another big theme in your book, and you have a great anecdote about Burt “The Machine” Kreischer where he enhances the truth to make his punchline work. I’m guessing that you wrote this book before the Hasan Minhaj scandal broke where he was distorting the truth, but it was to make a bigger point about racism in America. But it also betrayed trust of his audience. When is fudging the truth okay? When I first heard the Hasan Minhaj story, I was like, “Oh, you mean a comedian made up a punchline? Shocking.” But I understand the betrayal of trust. So where is that line?

I was really happy that story came out after the book was finished. That story taps onto a few things that I talk about. If that story came out, I would have to write about it in the book because it’s so obviously involved, but it doesn’t fit as neatly into one thing or another. It’s partly a politics story, and it’s partly a truth story. But the reaction to that story obviously is elucidating of how a lot of people feel and what people expect of comedians and where those expectations come from.

The thing about the Burt Kreischer story, so it’s not even that he fudged information to make it be funnier, the story about him befriending the Russian mafia broadly defined. It’s that he had this story that was true that he would tell on podcasts or to friends, and they’re like, “That is such an amazing story, you have to tell it on stage.” He’s like, “I can’t tell it on stage, it’s too long, there’s too many people involved, it’s too confusing.” And people are like, “You got to tell on stage.” Joe Rogan told his fans, “If you ever see Burt Live, if he doesn’t tell that story, boo him or something like that so he tells this,” whatever. I don’t even know if that story is true, Burt is a fabulist.

I love that word by the way because it sounds fabulous.

So he tells this story and it doesn’t work. It’s a long story, but it’s hard to know where the laughs are. You have the audience listening, they don’t know what parts they’re supposed to be laughing at. It ends and they don’t know it ends, so he has to carve out different things. He has these multiple characters and different scenes and he’s shaving them away. He has a friend with him throughout the entire journey that he does this story and he realizes, “I have to cut that friend out. Everything is just going to be from my perspective, I’m not going to say there was a person there. I’m not going to say there wasn’t a person there. You just won’t know.” That’s the number one thing comedians do when they tell stories is they limit the other people there to make it seem like a story they’re doing by themselves just because the audience cannot follow a two protagonist comedy story or it’s really hard.

But essentially he had a realization that the story wasn’t working because he was focused on trying to prove to the audience it was true because it was, and it’s a wild story. He would have these details and he’d be very specific, and he realized the audience doesn’t care about needing to be proved it’s true, they believe it’s true because he’s saying it, and what he needed was an ending that they felt was the proper ending to the story.

And the fundamental truth is still there?

Yeah, yeah, the fundamental truth of the experience and how that evolved, but he realized that the audience wasn’t feeling satisfied, they didn’t over react, so he had to change certain details.

He had to jazz up the kicker, yeah.

But it’s not just to make it funnier. [It’s] to make it more narratively compelling. So what is most interesting about that is all artists do that. Memoirists do that, and a person writing maybe a movie based on real life obviously would do that. The difference is a comedian is doing that based on audience reaction. So the audience is telling them what they think feels true. They’re laughing more because it feels more true to them than whatever other version of it. And then what often happens with comedians, because they’re telling the story so often, once a night for four years, they usually can’t remember what really happened. They now just have this sort of new thing that happens and that merges with what happened and it gets all confused up.

That is important context when you hear a story like the Hasan thing, because it’s not like he sat down and wrote those two shows, pen to paper and goes, “Oh, you know what? I should lie here. This place, I’m going to make up this lie. This lie will help be helpful.” I think probably a lot of these stories he worked on as singular pieces and the audience reacted a certain way and him and his collaborators decided, “Oh, these things weren’t working, those things weren’t working,” and, “Oh, they get it, but it’s not hitting them the way that I want them to feel. So what if we move the timeline of this over? What if we say my fear that this was anthrax, that’s not hitting the way that I want to do, I should say it fell on my baby,” because that makes the story sort of a more great story because that’s what it felt like when I saw that anthrax there. But the audience, if you just tell people they saw something that was anthrax on a table, but then it wasn’t anthrax, that’s not a good story. Now is that making it funnier? Not necessarily, but it’s making sort of it more narratively cohesive.

The thing is, when people said it broke the trust of the audience, it’s hard because I don’t know if it did because I don’t know his actual audience had a feeling one way or the other. I think a lot of people decided he broke the contract with his audience, but no one asked his audience. I feel like a lot of opinions about this story were people who didn’t like Hasan Minhaj being like, “He broke the contract to his audience.” What they didn’t ask was if that audience felt like the contract was broken with them. It’s a little bit condescending to his audience, assuming that they naively—

It’s also treating an audience like a monolith, which it isn’t.

Yeah, yeah, treating an audience like a monolith. And people also projected certain expectations on who this audience was. A lot of it was, and I think this is reasonable, this idea that Hasan played up racial prejudice to create favor with a white mainstream audience, which is not really who his audience necessarily was. If you go to Hasan’s live show, it’s not necessarily a white mainstream audience. There’s a lot of different things involved that I think are legitimate.

The thing that I think is most interesting as the dust settles on it is, so Hasan did a video where he explained his side to certain things and how The New Yorker did things that I personally, with my own understanding of journalism, I don’t know whether it’s allowed in terms of moving quotes around or cutting out certain parts of quotes that would further make their case. I believe The New Yorker was like, “We have enough other reporting to justify whatever we did.” But the thing that is noteworthy is that when he released that video, I thought everyone was going to make fun of it and then just be like, “Yeah, right.” But if you were online that day, most people defended Hasan. Quietly the people who were on the other side from the beginning were like, “I still don’t believe it.”

And what I realized is most people returned to where they were before the story even came out, which is if you liked him, you still like him, if you didn’t like him, you still don’t like him. And what is most telling, and again, to make this sort of a media story, is that people now believe who they believe, right? Now people have two completely different understandings of the truth, and that reflects a lot about where we are in terms of mainstream culture. As I said, the Hasan story is not just a truth story, it’s also a politics story, and part of that story is about how over the last 40 years, essentially my lifetime, people’s trust in the mainstream news has dropped an unbelievable amount. [In] 1976, it was like 75 percent of people trusted the news and now it’s like 30 percent, and that was 2016, I assume that number’s even less now. And in their place, a lot of people have come to the fore.

And it’s been well documented, the rise of the political comedy personified by the John Stewarts of the world.

Yeah, exactly. This played out that exact thing, which is people go, “This is why I never trusted mainstream media and this is why I’m going to trust this comedian’s version of the truth.” Or you have people like, “Why are we trusting a comedian? We should be trusting the news.” It is a weird time that this idea of truth, which I think for a very long time, people had a very secure understanding of what that word meant, is now —partly because of the internet, and as we said, people have their own ideas of truth — so far removed from any solid ground that now there’s just tribes of people and some people believe The New Yorker and their fact checking department and some believe Hasan Minhaj and his video production crew.

Yeah, and people pick the facts that support their side and they run with that. But this brings up to a degree this idea of tribalism. There’s even like internecine war among comics themselves. You cite a rant by Bill Burr about younger comics not having the chops to play in any room anywhere, they play to safe audiences. Marc Maron is pissed about how Jerrod Carmichael is playing with the format of the comedy special in a way that undermines the in-the-moment experience. Is that in line with what you were saying before? Or is this an example of, “Get off my lawn,” from older comics? Or have comics always side eyed each other?

Well, I think there’s a few things. I think this is mostly an example of that New Yorker story, which was written by a media reporter, not a cultural reporter, which is nothing against the article, but it does come off a little bit as, “How dare political comedians have the cred that we have?” And I also think journalism probably should be more trusted than comedians are, but it’s not comedians’ fault. Comedians will just fill a void. I think a lot of the tensions that exist in the book, and a lot of the things that I try to upend, does come from, there’s an insecurity that comedians have.

Well, that’s why they’re comics, right?

Yeah, yeah. That exists. They have that insecurity going into it. But I think even post the “comedy boom” went bust, there was a sort of culture that at any moment, society’s going to not care about comedians. And I think on a smaller level, I think there’s a lot of examples of you’re only funny to a wide audience or a person for an amount of time, the industry creates a scarcity mindset and they’re like, “We’re always looking for something new.” And so as a result, older comedians have to fight for relevance, and their way of fighting for relevance is to be like, “The way new people are doing it is wrong. Everyone doing it differently is wrong.”

And that always works.

Yeah, that always works, right? It’s not like time always marches forward. There obviously is a huge audience of people who think that, “Kids these days, blah, blah, blah.” The other thing is that Moshe Kasher once said to me that comedians are so insecure that what they do even is an art form at all they do attack anyone doing it differently because they’re scared that someone doing it differently delegitimizes how they approach it.

It means they’re doing it wrong.

Yeah. So then when they see someone do it differently, it’s hard for them to be like, “I’m okay still not doing it that way.” And especially if they’re older, it’s hard for them not to be like, “That’s been done before. Why is this person noteworthy? Everyone’s been doing this, blah, blah, blah, before.” I think honestly, when I talked to Marc Maron, we came to a realization that what is noteworthy when people do things that seem like they’ve done before is if a lot of people respond to it now. People responding to it is actually the thing that is noteworthy about a person doing something different. It’s not just like doing something different in a void, it’s that people respond to it, and that’s part of the equation as well. But comedians can’t think about audiences that way or have a hard time thinking about audiences that way.

And this comes up throughout your book because you show “SNL” as a mirror of culture — not necessarily a taste setter, but a taste reflector. The book is bookended with the beginning, Chris Rock writing on stage, working out his material on stage, and then John Mulaney at the other end writing on stage. This idea was so interesting to me that the audience is as much a character as the comedian.

I wrote this book for audiences, I didn’t write this book for comedians.

I was going to ask, who is this for? Yeah.

I wrote this book for comedy fans or people who are comedy fan-curious. Then I realized a lot of comedians are comedy fans, so then comedians have embraced the book the most.

Oh, and I’m sure you’re just going to get a lot of people reading it initially out of spite, like, “Oh, let’s see what this guy has to say.”

A few. But at this point, I’ve interviewed so many of them. But I, as an audience member, see what the audience does and how for good and for bad, you have a bad audience, if you have a bad fan base, your comedy gets worse. If you see Louis C.K.’s comedy now, it’s so much worse, partly because he’s playing to a worse audience who pushes back so little on a lot of the things he does. So it’s just less exciting in some ways or less dynamic.

It’s sad. You do a good point of laying this out, but before he was called out, rightfully so, for his misbehavior, he was so good.

He’s a talented person, but then there’s so many things that I think made his work get worse, not only just hiding that thing.

It is worse.

But just the idea that he also was putting out so much material before the story came out that I was like, “Oh, if you instead of putting out seven specials in that few years, put out one or two maybe it would’ve stayed at the level of the one earlier in the decade.”

But yeah, I think there’s a love/hate relationship, there is a co-dependent relationship. It’s not one thing, but I think a lot of the goal of the book is I want a better informed audience or more passionate audience because I think it results in better comedy. And so what I want to do is have audiences go to a show with greater expectations and greater personal investment. So they’re just like, “Oh, I think a comedian might do something great as a specific artist. I’m not just going to a show and I want them to do exactly what I want to do. This is not a service industry, I’m going to see an artist.”

I think a lot of the negative things that happened in comedy happen because the comedian is being defensive, because the audience is antagonistic towards them, so they’re creating a shell around them, they’re not sort of being vulnerable — and “vulnerable” can mean a lot of things. So they’re lashing out and maybe they get laughs from that lashing out, and then that sort of becomes what they do. And again, the internet is pushing against that, right? The internet is trying to get everyone to be the exact same thing. The algorithm turns everyone into sort of a robot in that way.

Well, it turns into everyone doing crowd work, right?

Yeah, yeah, everyone’s doing crowd work. To me, it’s like fighting for comedy’s soul, and I don’t know if it’s a winning battle, but I’m like, we have to at least try to return it to something.

Would you say we’re at a crossroads, we’re at a scary point where you say fighting for its soul?

It’s hard to say “crossroads.” If you look back, how Louis [C.K.] returned was a crossroads, and I think if he acted differently, comedy would be in a very different place. A lot of comedians across the spectrum of beliefs, political beliefs, but also sort of social, gender role, gender norm beliefs have privately or publicly said some version that, when Louis came back, there was a real opportunity. If he was the comedian everyone thought he was in terms of how he spoke about himself and society or something, he had real potential to talk about what happened in a way that could have helped people move forward together.

Because he denied it at first? He did admit it at a certain point.

Yeah, he did admit it, but then when he talked about it, he didn’t talk about it in his comedy really at all. And then when he did, the joke I think he had in his first special was just something about, “Oh, did you ever lose $25 million in a day or something?” It just became a defensive. He was the victim of all this stuff, and he didn’t really get into it. And a lot of comedians thought that was a tremendous missed opportunity to maybe create some sort of collective conversation around this with people who maybe come from different perspectives. He probably made a calculated decision where he goes, “I’m not going to get back a lot of the fans that I had who were hurt by my actions, but I got a lot of fans who kind of were fine with it anyway, and I have kids that need to go to college, so I’m just going to do the most cynical version of it.” That was a crossroads. Hypothetically, he could have pushed comedy maybe forward in terms of how they talked about the Me Too movement and stuff. Instead, he helped strengthen the sides when you say there’s a comedy civil war. It’s the same battles or whatever that are happening over and over again.

They’re flashpoints though.

Yeah, yeah, they’re flashpoints. So it’s like Dave Chappelle’s return or every time Dave Chappelle exists, it’s sort of some version of that. And Matt Rife is our new flashpoint.

Yeah, I was going to ask you about him, but I don’t know if he might be too deep in the weeds.

It is all the same sort of conversation that are happening. I think Matt Rife is built in a lab out of this. He’s forged in the fire of these conversations.

He’s forged in the fire of TikTok and definitely not plastic surgery.

Well, I won’t say that. He’s a conflation of sort of embracing the algorithm and being a sort of ambition machine being like, “I’m going to embrace what is popular,” so then you see him do it and it works that way. Well, of course that’s going to happen. He embraced sort of how TikTok trends were working, he was embracing sort of what Dave Chappelle was doing, who’s the biggest comedian in the world.

What is so weird about this example is he’s like a photocopy of a photocopy of these trends. He is not it, he’s an avatar for these conversations. As I describe Matt Rife, it’s like hopefully he’s the Antichrist. His comedy is so unlikable to a lot of people. Not that he’s not famous, he’s going to be famous. He already is. But that enough people realize a lot of this is kind of hacky and bad, we need to stop doing this. We should maybe not do every crowd work video, we’re cynically playing into algorithm. Maybe we don’t need to do cheap offensive jokes because it kind of is lazy. Dane Cook was a unifying figure for a lot of people who decided, “We’re going to be not Dane Cook.”

Yeah, I was just going to ask, is he the new Dane Cook?

In that way, he not always is so different from Dane Cook. He’s so clearly fills the same sort of space, and I think Dane Cook was really useful in terms of creating a robust alternative comedy movement that I think currently is lacking because I think a lot of the potential alternative comedians haven’t moved to cities yet, or maybe they won’t because they graduated college out of the pandemic and they’re like, “Oh, maybe I actually don’t need to do live.” Who knows? There’s a lot of little reasons why alternative comedy isn’t where it was. Maybe this is what’s going to change it, where people go like, “Oh, well, I don’t want to be that. What’s the alternative to that?”

I don’t want to end on Matt Rife. I loved the part of the book where you go and see Las Culturistas at The Bell House. I guess they’re not alternative anymore because they’re all famous now, but the rise of the queer comic scene, the BIPOC comics, is very exciting.

Anytime people go like, “Are you nervous about the future of comedy?” And periodically am, but then I remember that in the past when I was nervous, something happened that it made me not nervous or excited or whatever. And so the example that I have, and maybe it was seven years ago, it’s 2016, so whenever that was, seven years ago.

It’s hard to do that math. But yeah.

I was like, “There aren’t new comedians, everyone’s doing the same thing. It’s going to slowly dwindle. We’ve reached the sort of culmination of whatever movement we’re at.” And I hadn’t gone to a show in a while and I saw [a listing for] Las Culturistas. I saw a show at Littlefield that had 50 comedians on it, that’s the reason I went. I didn’t know any of the comedians. I just saw 50 comedians, I go, “This will be an opportunity to see who the new comedians are.”

See, most people would look at that and say, “I don’t know any of those names. They must not be funny.”

Honestly, it was just sort of like, I only go out so much. What an easy way to learn who comedians are.

A lot of people one point, yeah.

And there’s the curiosity of what is going to happen with 50? Where are they going to stand? Littlefield only holds 200 people or something like that. Is half the audience going to be performers? In some ways they were, but that’s a side story. So I go. The show’s called “Las Culturistas I Don’t Think So, Honey Live.” I don’t know what any of these words mean. And I go. There’s a story that is burned into my brain from some TV documentary about Sumner Redstone who was the CEO or the founder of Viacom or whatever. He was seeing “Star Wars” for the first time opening night or opening day, and the first 20 minutes happened or 10 minutes, he leaves in the middle to go buy 20th Century Fox stock because he goes, “This is the future, whatever this is.” And I think about that all the time. The only other time that’s happened to me is I saw Bon Iver live before the album came out.

I saw him early days.

I saw him early days. He was the opener so I was like, “Maybe we should leave right now and email his team?” I was with somebody, so I was like, “Maybe I’ll wait the show and then email his team when I get home.” I saw [Las Culturistas], I thought to leave in the middle to reach out to them. I was like, “Well, nothing’s going to happen overnight.” But I did reach out to them the next morning to be like, “Do you want to do things for Vulture?”

But anyway, so these two guys, Bowen Yang and Matt Rogers are special. They’re special together. They created a space that allows 50 comedians to thrive with a certain sort of perspective that I had not seen in comedy before. And I want to be clear, because I think often people are like, “Oh, now there are gay comedians, and there weren’t gay comedians before? There’s comedians of color.” Because obviously there were, though there were fewer gay comedians, comedy was very antagonistic to the existence of gay people for a very long time. Gay male comedians.

“RuPaul’s Drag Race,” we probably could do a whole segment on that and their impact on comedy.

There’s a lot of cultural acceptance of it. The thing that I think became clear is that it’s not just they were gay comedians, they were queer comedians. They were intentionally pushing against the norms of comedy, offering a new perspective on what alternative comedy can be, be it how they approach characters, how they approach ideas like truth. Truth from a queer theory lens is fractured, if you think about how drag queens think about what “real” is is so different. Are you real when you’re in makeup? Are you not real when you’re in makeup? Who is the real person? All that stuff.

What is “realness”?

This was sort of the culmination to what the alternative comedy project was building towards, which was allowing comedy to be changed and not really have the same vocabulary that exists in alternative comedy in the past. So now, though, a lot of those comedians are famous. Ziwe was on that show that night, but Julio Torres, and I’m trying to think of comedians from that scene.

So I find myself again at this feeling of where are we? We kind of did that already, that was seven years ago. I can’t be like, “The new thing is a thing that I saw seven years ago.” I mean, Bowen has been on SNL for four years. And I don’t know what’s next, but I do believe there’s something next. The benefit of being older and now following comedy professionally for 12 years and personally for, whatever, 30 years is: something appears. I just haven’t found it yet. Hasn’t appeared in front of me. I’m not in the right space. I haven’t gone to parts of Brooklyn that are off trains I’m not near so then maybe it’s happening there. The fact that I live in Central Brooklyn makes it really hard because what if everything is happening in Ridgewood, Queens? It’s like it’s so hard for me to get there. What I know is it’s probably something is happening and I just need to find it.

You got to get to Bushwick more.

Yeah, yeah. I have to accept that Bushwick was for my twenties. I have to go there still as I get towards my forties. That’s where I find optimism, which is that there will be something next, because there always has been. I know enough about the history of comedy to know that there always has been something exciting.

People are going to want to laugh, people are going to want to make people laugh.

Oh, and people are laughing now. It’s so funny to always be negative about it. Comedy is more popular than it ever has been, but people will be like, “It’s almost over,” or, “Comedy’s dead.”

The world is literally ending all around us, we need something to take our minds off it. I mean, we’re running low on time, I recognize, but this is a very personal book for you. Comedy played a role for you in terms of getting through grief and connecting with other people, and I think that that is probably a universal truth.

There is something about being an audience, and there’s other art forms have audiences and those things are special, but there is something really unique about how an audience comes together with laughter and how comedy works, which is really you as a collective decide what is funny in a way that is not exactly who you are as an individual. And the comedian is reacting to that because the comedian is reacting in the moment and they’re creating in that moment. Other art forms, there’s jam bands or whatever, they can say they’re creating in the moment.

You get your Phish joke in, yeah. It’s the moment, you had to be there.

Yeah, and there’s something about that moment, the ability when it really works to be one thing with 200 people, that is a connective thing at a time where we’re in a very fractured time, in a time when we are more than ever separated, in a time when we’re post-pandemic where we were physically not allowed to see each other or not supposed to see each other. I would say literally right now, it’s been however many years since the most lockdown phase, it does feel like audiences are kind of starting to remember what it’s like to be an audience, and you feel that difference. This is why we’re doing it. This is a special thing. This is actually the main reason we’re alive.

I just saw Reggie Watts at The Bell House a couple of weeks ago. You mentioned him [in the book]; you saw him at a critical point. By the end of it, you’re like, “I don’t even remember what I just saw, but it was cathartic and it was moving and it was hilarious.”

And you’re a part of it. And you can’t describe it. I mean, his show, if you try to describe one of the things that happened, it would be so weird. And so evolutionarily comedy is rooted in a certain feelings of trust and safety.

Play theory.

Play theory, right? So if you think of us laughing, it’s not that dissimilar to why chimpanzees laugh or dogs laugh and it’s sort of playing around with each other, and that demands trusting the people you’re playing with. Being at a comedy show is like tricking your brain into thinking you’re with your friends. So there’s something really beautiful about, “Oh, I’m with 200 strangers, but they’re my friends right now because we’re all laughing together.”

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like