"Gowanus dolphin" by pardonmeforasking is licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The ballad of Mucky, the unlucky Gowanus dolphin

An excerpt from the book 'Wild City' reveals some of the polluted history of the Gowanus Canal through the sad story of a stray dolphin

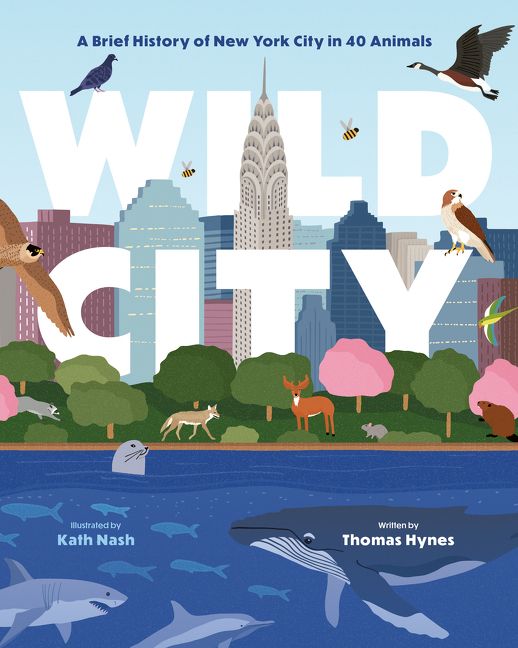

The following is an excerpt from “Wild City: A Brief History of New York City in 40 Animals,” by Brooklyn writer Tom Hynes. The recently-published book tells the surprising history of animals and wildlife of New York City, from refugee parrots and prodigal beavers to gorgeous Fifth Avenue hawks and vengeful groundhogs. This is the story of a less fortunate marine mammal.

New York City’s dolphins are a cheerful reminder of how much environmental quality has improved. The water is cleaner. There’s more food for them to eat. There are even boats offering dolphin sightseeing tours, though standing on the shore near Coney Island is itself a pretty good opportunity to spot the joyful marine mammals. Generally, it has been good news for the city’s dolphins.

New York City’s dolphins are a cheerful reminder of how much environmental quality has improved. The water is cleaner. There’s more food for them to eat. There are even boats offering dolphin sightseeing tours, though standing on the shore near Coney Island is itself a pretty good opportunity to spot the joyful marine mammals. Generally, it has been good news for the city’s dolphins.

However, the unlucky local dolphin who wandered into Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal in January 2013 was a reminder of how much cleanup remains to be done. The dolphin, whom the locals nicknamed Mucky, was old and very sick when he arrived. He was separated from his pod, clearly lost, and stranded in the worst possible waters.

The Gowanus Canal was originally the Gowanus Creek. Legend has it the oysters there would grow to the size of dinner plates. The creek was fed by nearby water flowing downhill from the appropriately named Prospect Heights, Cobble Hill, and Park Slope.

The Gowanus Creek also played a major part in the Battle of Brooklyn during the Revolutionary War. In fact, some unaccounted for American soldiers from the First Maryland Regiment are still buried in the surrounding neighborhoods. Nobody knows where exactly.

In the 1860s, the creek was transformed into a 1.8-mile canal, running from Red Hook to Boerum Hill. Almost immediately, it was both a commercial success and an ecological nightmare. For starters, the streams and tributaries that once flowed into the creek were plugged up, effectively cutting off oxygen to the waterway. The city replaced this flow with raw sewage to try to flush out the canal, later replaced by combined sewage overflow, which accounts for the ongoing pollution to the canal. Plus, there were all those decades of heavy industry conducted without a whiff of environmental oversight.

By the 20th century, the canal was found to have high levels of pesticides, mercury, and cancer-causing PCBs. A ten-foot layer of industrial sediment known as black mayonnaise lined the bottom. (It’s where Mucky got his name.) Plus, any time it rained, raw sewage from adjacent neighborhoods would be added to the mix.

As Eric Sanderson, author of “Mannahatta,” told an audience at the Brooklyn Historical Society in 2018, “nobody paid to clean up the mess they made.” Locals sarcastically renamed the canal Lavender Lake, referring to its unnatural appearance and color. Its putrid waters stood stagnant for decades, and—no surprise—it smelled terrible. It wasn’t until a flushing station was repaired in 1999 that the waterway had any movement to it. Suffice to say, it was not a very conducive environment for wildlife.

Eventually, the EPA designated the Gowanus Canal as a Superfund site in 2010, meaning the federal government saw the waterway as a candidate for cleanup based on its threat to human health and the environment. In most places, this sort of ignominy might deter real estate speculation, but not in Brooklyn, baby. The shore of the canal is lined with wedding venues, restaurants, and bars, making it more of a “super fun” site. There is even a Whole Foods. The cleanup had barely begun and developers were already dreaming of the new Venice of Brooklyn.

A murky screenshot of Mucky from YouTube

Sadly, Mucky the dolphin didn’t last long in the canal. He died a day after arriving. A necropsy indicated that he was very old and pretty sick when he got there. Even if the canal’s toxic waters weren’t directly to blame, they certainly didn’t help. But cleaning up is a process. It won’t happen overnight. Every so often a sad reminder will float to the shore reminding New Yorkers of how much work remains.

However, by all indications, the future of the Gowanus Canal is one of a healthier waterway.There are already some signs of recovery. Oysters, white perch, herring, striped bass, crabs, jelly-fish, and anchovies have all returned, though their life expectancy is about half the length of animals that don’t live in a Superfund site.

Leading this turnaround is the Gowanus Canal Conservancy. They see a multifaceted approach, including regenerating the urban forest, planting absorbent gardens, and incentivizing green roofs to minimize storm runoff. They are also planning for a future of pedestrian esplanades, kayak launches, and loads of new open spaces. There’s also some talk of daylighting Brouwer’s Brook, a buried stream that once flowed above ground and now flows in the Conservancy’s own basement.

Andrea Parker, Executive Director of the Gowanus Canal Conservancy, believes the underlying ecology, geology, and hydrology of the site need to be understood and even embraced as the site evolves into its next iteration. She laughs it off when people suggest simply filling in the Gowanus Canal with dirt. “Well then the entire neighborhood would flood,” says Parker. “We need to accept that this is where the water goes. It’s a really rich and vibrant place because of that. And we need to embrace it and celebrate that.”

Improving the canal will not only help the neighborhood, but also the greater harbor. That’s great news for all species, including dolphins, and not just the ones that get lost in the canal.

You might also like