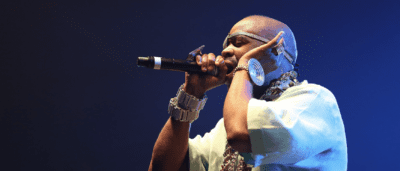

Photo by Gabriella Canal

Life on the roof with one of Brooklyn’s last pigeon keepers

José Ingles keeps 500 birds that he flies from his roof in Bushwick—so that he can stay rooted to himself

José Ingles remembers staring anxiously into the evening sky from the roof of his childhood home in East New York, looking for any sign of his 120 pigeons.

“I thought I had lost them.”

It was his first flight as a pigeon breeder and “flier,” and the rush of excitement he felt when he released his flock two hours earlier had vanished. His mind raced through different scenarios—maybe they were attacked by a falcon. Maybe they’d landed in another breeder’s coop. He had spent weeks perfecting his own coop, making it a comfortable home for the birds.

“I was real upset,” he recalls. “But they shocked me, they came back.”

Ingles, who was 15 at the time, spent that summer of 1996 on rooftops learning his flock’s ways, an escape from the streets below where friends were involved with drugs or violence.

“It was rough,” he says, his voice gravelly from years of smoking. “They called me boring, they called me a chump. But let’s put it this way: the pigeons saved me.”

‘The shit we do for birds’

Ingles was 8 the first time he held a pigeon. It belonged to his uncle, who cared for his own flock. Ingles grew up never knowing his father, but “my mom was a hustler,” he says. “No matter what we were going through, there was always a meal on the table.”

She had Ingles at 13, then four more children, whom his uncle helped raise. When he became ill, his birds became Ingles’. At first, he didn’t care much for them, but then he began to notice how they would flutter when they saw him, how their feathers reflected different colors during flights.

“I fell in love.”

Almost 20 years later, Ingles has grown that flock to 500 pigeons. He calls them The Stanhope Bullys.

The stairwell of one of the colorful row houses on Bushwick’s Stanhope Street echoes with cooing. Feathers litter the skylight above.

“By 6:30 in the morning you can hear them ‘brrr’,” Ingles says, carrying a 50-pound bag of feed up the steps. “I’m surprised the tenants don’t call me complaining.”

Inlges and one of the Bullys (by Gabriella Canal)

Ingles, now 40, is the building’s superintendent, sweeping the floors and taking out the trash three days a week. He’s also always on call as an ironworker, erecting columns and beams of steel hundreds of feet above Manhattan.

“We build skyscrapers from scratch,” he says. “And all we got is a harness on us.”

On the third floor, balancing the bag on his right shoulder, he makes his way to the roof hatch and throws the bag down. “The shit we do for birds.”

The roof is neatly lined with brooms, shovels and feeders. Security cameras hang from two black coops. From the smaller one comes a harsh scraping noise, like metal against wood. A man appears in the doorframe and calls out to Ingles.

“Hey J-Rock, they’re grabbing straws already,” he says, referring to the hay on the floor that the pigeons use for nesting.

“They’re ready, baby.”

“It’s amazing. You knew they’d get the nests ready.”

Hector Cabrera, 63, met Ingles in September, at a bird auction in Long Island, and has become his new partner.

“He’s got his section, I got mine,” Cabrera says. “Nice to have the company of another person. It’s a lot of work—when one can’t, then the other can.”

They spent months building Cabrera’s coop, finishing late January in time for mating season. Cabrera, a school bus driver, has been caring for pigeons since he was 11; he worked at a pet shop in Bensonhurst whose owner kept a coop on the roof.

“That’s where it all started.”

Today, he owns 250 birds.

“José and I decided to let some of each other’s flights mate,” he says. They hope to have 500 babies by the spring.

“I would like to have young blood in here,” Ingles says. “I’ll sell the old ones at auction, or give them to a few friends who are starting up. I just want to keep the hobby alive.”

A hobby in decline

Ingles is known as a “flier,” raising pigeons to play a competitive game of “catch-keep,” capturing stray birds from neighboring coops with his own. In New York, the tradition of rooftop flying dates back around 200 years, says Colin Jerolmack, an environmental sociologist at New York University and author of “The Global Pigeon.” It originated in white immigrant communities and was passed on to communities of color at the end of the 20th century.

“The patrilineal tradition was broken,” Jerolmack says. “Most of the pigeon fliers’ kids moved out to the suburbs and the ethnic whites who stayed behind needed help, recruiting mainly Puerto Rican and Black people to help on the roof.”

Today, Jerolmack estimates only about 300 pigeon keepers remain from the thousands there once were, blaming gentrification for the decline.

“The hobby’s alive but it’s on life support,” he says. “It’s hard to say if it will survive another two generations.”

Ingles’s phone rings and he grabs a carrying crate, carefully placing 10 pigeons inside. He heads downstairs and returns with $200: a retired friend from New Jersey was looking to get into the hobby.

On average, Ingles spends $500 a month to maintain the birds, an expense Cabrera now shares.

“It’s not just food and water,” Cabrera explains. “You’ve got to give them electrolytes and the proper medication.”

In fact, Ingles is pouring bright red beet water—a source of electrolytes—into the watering canisters. “José’s a very good caretaker of pigeons,” Cabrera adds. “He’s not afraid to get his hands dirty.”

Ingles ducks into his coop, startling the pigeons who begin to flap their wings, darting across the space. Dust blooms, perfuming the place with sawdust and ammonia. In symmetrical cubbies stacked against the walls, some pigeons are beginning to pair up. Ingles scatters more straw on the floor, and a few birds collect the pieces and bring them back to their cubbies. Most are organized by breed, brown and white birds on one side, black speckled pigeons on the other.

“We got beauties in here,” Ingles says. His eyes turn bright red and begin to tear. He sneezes. “Salúd,” Cabrera calls out.

“I’m allergic to feathers,” Ingles explains. “It can take me to the grave, I don’t mind. This is something I love to do.”

At one time, this was all Ingles was doing every day. He began to miss weekends and vacations with his wife and four daughters.

“My mom and I actually got into an altercation,” he says. “Said I was giving more time to the birds. She told me, ‘Why don’t you just take your mattress up there?’”

Ingles and his wife eventually separated.

“She didn’t understand the feeling that I have for them.”

Over the years, he’s tried to share that feeling with others. It led to his meeting Mike Tyson and Martha Stewart, who also keep pigeons. It brought him onto the set of “The Irishman” and introduced him to basketball star, Carmelo Anthony.

He opens the door of the coop wide and with one high-pitched whistle, the pigeons suddenly burst into flight, diving and circling in graceful patterns. Ingles stops and looks up.

“This is my therapy,” he says, with a cup of coffee in one hand and a cigarette in the other.

The roof hatch opens for another friend, Aaron Marshall, 64, who has known Ingles since he was young. He shows off his new binoculars.

“They adjust to each eye,” he says. “Fog resistant too.”

Suddenly, there’s a loud commotion and the three run out to find a pair of falcons diving towards the pigeons.

“They’re panicked,” Marshall explains. They all begin to call the birds back with whistles and the flock floats down to the roof. Ingles notices one has a different color leg band. It’s a pigeon from a neighboring coop, swept up during the chaos.

Six of his and Cabrera’s birds had gotten swept up by neighboring flocks the other day. “It’s the name of the game,” Ingles says. “You catch, you lose.”

He holds the bird in one hand, checking its feathers before feeding it.

“Without this, what would I do?” Ingles asks. “Who would I be?”

Photo by Gabriella Canal

You might also like