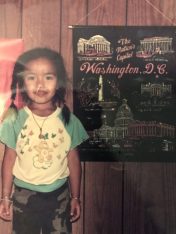

Somboun as a baby in a Thai refugee camp, courtesy April Somboun. Photo illustration by Jessica Ulman.

Opinion: I am not your ‘model minority’

Asians and Asian-Americans like me, who came to this country as a refugee, can no longer afford to be silent on violence and hate

I was born in a refugee camp to a single mother who fled Laos, her home country, to escape communism, and a regime that wanted to do us harm. Now, hate, violence, and fear are happening in diverse U.S. cities like ours. And I won’t stand for it.

My mother and grandmother fought hard to bring us to the U.S. For mom, achieving the American Dream meant learning English, so we could begin to be a part of the melting pot we called “home.” It also meant working multiple jobs and never taking a day off, so she could pull us out of Section 8 housing. For her, our Section 8 apartment, Food Stamps, and other services were meant to be a hand-up — an opportunity for us to get on our feet and get ahead.

For me, achieving the “dream” meant going to the local public school and learning all about this new country — its language, culture, and history. And, like my mother, it meant working hard. I remember working in my elementary cafeteria to get free school lunches so I wouldn’t have to burden my mother with another expense. Every summer I woke up at 5 a.m. so I could spend the day picking berries in the hot sun, for less than $5 a day. We supplemented our meals with fish we caught in the Columbia River, right near our home in Washington State.

Somboun at 4

Keeping pace and becoming a ‘model’

Despite working so hard to get ahead and assimilate, though, I was living in two worlds—and my classmates made sure I knew it. On the morning bus ride, they’d tease me for eating sticky rice and jerky, the opposite of an “American breakfast.” My KMart clothes didn’t look like their trendy outfits. No matter what I did, I wasn’t “American enough.” It felt like, no matter where I turned, I was an outsider—and, worse, I knew people wanted me to feel that way.

Despite the hurdles, I worked hard to find my way. I practiced English anytime I could. When my mom was working, my grandmother would pick me up at the bus stop—we’d go home where sticky rice was waiting for me, and we’d watch “Days of Our Lives.” This was one way we both learned English—and the better I got, the more I became her translator, helping her at shops and doctor’s appointments.

Over time, we made considerable strides, moving out of Section 8 housing and away from Food Stamps. I’d also achieved my goals—I was a high-achieving honors student. I knew education was my pathway out of poverty. I knew, as my mother said over and over, that people can take your belongings but they can never take your knowledge.

While our collective hard work and unrelenting focus had paid off, this shift wasn’t without its own challenges. Suddenly, we were seen as the picture of a “model minority”—and that was problematic, too.

A model of racism

Many interpret the term “model” as a positive nod towards Asian-Americans’ collective success. Yes, the research shows Asian-Americans tend to be among the highest-educated and highest-earning populations in the U.S.—but that’s just part of the story. The model albatross completely overlooks the racism and violence towards Asians and Asian-Americans. In 2020, hate crimes against Asians were up 1,900 percent here in New York City. What’s more, these crimes overwhelmingly target women. Of the nearly 3,800 reported incidents of anti-Asian hate crimes in the last year, nearly 70 percent were against Asian women.

The notion of a “model minority” also overlooks the poverty piece of the conversation. Asian-Americans have a 12.3 percent poverty rate. It also ignores the fact that close to 43 percent of Asian-Americans live in “linguistically-isolated” households, where no one older than five is proficient in English. Asking for help, reporting threats, denouncing hate crimes, and seeking support is, in many cases, not an option.

Already, it was a perfect storm. Former President Trump’s ongoing rhetoric, though, made it even worse. Throughout his term, Trump spewed racist messages surrounding everything from immigration to Covid-19—and, with each speech or off-handed remark, he fanned the flames of anti-Asian sentiment and outright violence. His exclusionary policies forced people around the globe to stay in their home countries, no matter the violence and imminent threats to their lives and their families. And his constant references to the “China Virus” and “Kung Flu” incited countless Americans, desperate for answers—and desperate to place blame.

Now we’re here, in a moment in time when Asians and Asian-Americans are scared to walk down the street for fear they’ll be the next victim. Last week, that terror reigned down on six Asian women in Georgia—mothers, daughters, sisters, community members who, in an instant, became part of this horrifying statistic. These women could have just as easily been my mother, grandmother, aunt, or cousins. These women could have been me.

Where do we go from here?

Today, I’m a mom of two young children, living in Brooklyn Heights—and my mother’s powerful drive for change is still central to my life and my work. I earned my master’s degree at Columbia University. I’ve had a long career in media, marketing, nonprofit, and business development. I’m active in my community and support nonprofits that help children and their families live and work with dignity.

In Brooklyn and across the state, there is only so much government can do to curb the hate. We as individuals must stand up for our Asian friends, neighbors, and community members.

In part, that does start by voting for more diversity at the local level. We are a diverse city and we need more elected officials who represent traditionally underserved communities, including the Asian population. Representation matters.

My mother still works in an assembly plant. She has mediocre health insurance, but she hustles by cooking lunches for friends and continues to work with no complaints. She’s also my grandmother’s primary caregiver. She will never lose her intense desire to move forward—to achieve and experience more.

I am proud of my story and the grit, determination, and perspective I gained growing up the way I did. But, at the same time, my mother—and millions of other Asian immigrants—came to this country and this city to flee oppressive regimes who wanted to do us harm. The fear-mongering, hate, and violence have no place here. Because, here, the only “model” should be how we treat others — and how we take a stand to protect our friends and neighbors when they need us most. For Asians and Asian-Americans, that means no longer being silent. We must step up and speak out right now.

You might also like