Photo illustration by Christophe Marchand

Topps at 70: Inside Brooklyn’s cardboard billions

A look at the baseball card-company's Sunset Park roots, the fabled '52 Mickey Mantle and today's collecting boom. Or is it a bubble?

Last August, five months into the brutal pandemic summer, millionaire entrepreneur and actor Rob Gough was flipping through his boyhood sports card collection. Mostly, it was a stack of crap, baseball and basketball cards from the late 1980s and early ’90s. One of them, however, caught his attention. For some long-forgotten reason, Gough had slabbed it inside a hard plastic case, screwing it down for maximum protection. It was a replica of the iconic 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle, one of the rarest and priciest baseball cards in the world. It, too, was worthless, but it got him thinking.

Having amassed quite a bit of disposable income throughout the decades—you might be familiar with Gough’s former-fashion-line-turned-CBD-brand DOPE—Gough started building up his childhood collection again during Covid, buying all the expensive cards he could never afford as a kid. By the time August rolled around, “I was over $10 million deep,” he tells Brooklyn magazine. But something clicked when he saw that Mantle. “Why am I buying all this stuff, and I don’t know what I’m doing?” That’s when he knew he needed to have a real ’52 Topps Mantle of his own, in as pristine condition as possible, price be damned.

And that’s exactly what he found.

Rob & Mickey (courtesy Rob Gough)

This past January, when millions of people were stuck at home with nothing better to do than put extra hours in at work and surf the internet, Gough thrust himself into the national spotlight by purchasing a ’52 Topps Mantle card, graded 9 out of 10 by Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA)—a third party company, which for a fee, inspects, authenticates, provides a condition-based number grade, and encases a collector’s card in tamper-resistant plastic—for a staggering $5.2 million, a record price for a baseball card at the time.

Gough is neither the first collector to spend millions on a ’52 Topps Mantle, nor will he be the last. Collectors have been coveting the card for decades, its desirability helping to transform what was once a child’s hobby in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s—think: bicycle spokes and shoe boxes—into a high-stakes game, only playable by the wealthiest of individuals, who keep their pristine, rectangular cards squirreled away in bank vaults.

Blame it on Topps. Once based in Sunset Park, the former tobacco company jumped headlong into the baseball card business 70 years ago this year. Now, with the post-Covid card market going bananas and investors champing at the bit, Topps is sitting on the precipice of a billion-dollar fortune. And it owes the entirety of that fact to its Kings County roots.

From the bottom to the Topps

Though the Topps Company can trace its roots back to 1938, when Brooklyn businessman Morris Shorin’s kids—Joseph, Ira, Philip, and Abram—pivoted the family’s failing tobacco business into a bubblegum empire, its baseball cards wouldn’t show up until 1951, the year Brooklyn was in the grips of Dodgers fandom. (By then the company had upgraded its tiny space in Williamsburg’s Gretsch Building to a larger one at 237 37th Street in Sunset Park at Bush Terminal, blocks from the Brooklyn waterfront.)

“Everybody in Brooklyn in those days loved ‘Dem Bums’ in Ebbets field,” Abram’s son Robert told the Associated Press in 1990. “And, one of [Abram’s] nephews came to him one day and said, ‘Uncle Abe, why don’t you put baseball cards in your gum?”

The baseball card had actually been around since the mid-to-late 1800s, though it had never served as more than a miniature billboard, hawking sporting goods, tobacco products, and candy. Because of widespread gum rationing during World War II, by the postwar era, it had become the candy of choice among children—nothing stokes demand like scarcity—and big-time producers like Leaf, Fleer, Bowman, and Topps, were much more interested in churning out gum sales than focusing their energies on the gimmicky baseball cards that were included in packs as a mere incentive to buy more. For that reason, by the late 1940s, the baseball card was decidedly meh, aesthetically. Most cards featured either a black-and-white or flat color portrait of a player painted on the front, with his name, a brief bio and requisite gum ad, written in a staid, monochrome font, on the back.

But the Shorins had other ideas, and in a serendipitous move, paired 28-year-old Bronx-born sales temp Seymour “Sy” Berger with Brooklyn-born creative director, Woodrow “Woody” Gelman, eight years his senior, to bring the Topps baseball card to life. Landing the gig through fraternity pal Joel Shorin (Philip’s son) after a brief but successful stint in sales at a luxury Manhattan department store, Berger was a recent World War II veteran, sporting an accounting degree, with designs on a career in sales (he’d later ascend to the title of vp of sports and licensing at Topps). Gelman, on the other hand, was kind of a legend at the company already, having previously done stints at DC Comics and doing commercial art, before landing at Topps, where he’d help the company dream up Bazooka Joe, a gum-selling juggernaut.

Berger and Gelman began spitballing ideas, and circa 1951, they believed they’d cracked the code. It was a fortuitous year in baseball, especially for New York City teams, with a trio making a bid for the World Series—the aforementioned Dodgers, along with the New York Giants and New York Yankees. That fall also marked the first national network sports telecast, with the best-of-three playoff between the Dodgers and Giants airing on TV to audiences across the country (it would famously end with Bobby Thompson’s “Shot Heard ’Round the World,” and the Giants winning the National League pennant; they would eventually lose to the Yankees).

Modeling their cards after those you might find in a poker deck, Berger and Gelman landed on a simple design, including not much more than the player’s name, a brief bio and black-and-white visage on the front and nothing of note on the back. The first series featured a red color scheme, the second, a blue one. Because arch competitor Bowman had exclusive rights to including gum in their packs of cards, Berger and Gelman were stuck with taffy, which was produced in a similar manner. Without gum to drive sales, though, Topps’ ’51s were DOA; plus, the taffy stuck to the cards. Kids turned their nose up at them, and sales were pitiful. “We had a calamity,” said Berger.

Now in full-on job-saving mode, Berger invited Gelman over to his Alabama Avenue apartment in Broadway Junction, and the two went back to the drawing board at Berger’s kitchen table. Using little more than his creativity, a ruler, scissors, colored pens, and cardboard, Gelman transformed Berger’s ideas into the design that would soon be heralded as the modern standard for baseball cards. Their prototype included a larger-than-average size, with Kodak Flexichrome–colored photographs of each player, along with the player’s printed name and facsimile autograph on the front; and on the back, the player’s biography and most importantly, his previous year’s and lifetime statistics, hand-calculated by Berger, who was putting those accounting chops to good use. The stats were key; they gave kids the mathematical proof that their favorite players were either knocking the stuffing out of baseballs or embarrassing batters at the plate.

The packs, which contained six cards and a stick of gum, were an immediate hit among the era’s kids. Berger’s hide was saved, and the 1952 Topps series’ first and second runs sold like hotcakes. So the young salesman pushed the Shorins to expand the set and produce a late-season run, which they green-lighted but produced at a much more limited print run. It turned out that his bosses had been right to be wary: By the time the high number series was released in stores, kids had already turned their attention over to football, and many shops began returning their unsold inventory to Topps’ Brooklyn factory, now located at 254 36th Street. Berger, ever the salesman, wouldn’t accept failure, taking the unsold inventory on the road, hawking it at carnivals for a penny a card, and later, 10 cards for a penny. But it was mostly in vain; approximately 300-500 cases of the 1952 cards were left over, and the only place to put them was in storage at the company’s Bush Terminal factory.

And there the cards sat for nearly a decade, collecting dust, and above all, symbolizing what happened when you got a little too big for your britches. Circa 1960, though, as legend has it, Berger decided to host a funeral at sea. He reportedly boxed up the remaining cases of ’52 Topps cards, each of which held 24 boxes with 24 packs apiece inside them, and loaded them onto three garbage trucks. The trucks were then driven onto a barge that was ferried out into the Atlantic Ocean, just opposite Atlantic Highlands, NJ. The boxes were then stacked in the center of the barge, a switch was flipped, and like something out of a carnival ride, the bottom dropped out. The cards tumbled into the depths of the Atlantic Ocean. Good riddance.

Aerial view of Bush Terminal and piers, looking South East

A childhood hobby grows up

While it’s impossible to put an exact price tag on what those drowned cases might be worth at auction today—some historians believe the card-dumping story to be utter bunk, going with the much less sexy claim that the ’52s were shipped off to Canada somewhere—a ballpark estimate would be well over $1 billion, according to Chris Ivy, director of sports auctions at the Dallas-based Heritage Auctions. “An unopened single box of 1952 Topps high numbers would sell in the $1.5 million–$2 million range,” says Ivy, “so if we extrapolate that out to a 20-box case, we would be looking at $30 million–$40 million range per case.”

Topps’ 1952 high number series includes a number of future Hall of Famers in it, including the Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson and the Yankees’ Mickey Mantle. It’s the latter that’s the key card in the series, and interestingly, it’s not even Mantle’s first (rookie cards normally sell at a premium): Topps’ competitor, Bowman, landed the rookie outfielder’s contract and the bragging rights in ’51, the year of Topps’ big failure and Mantle’s first of seven World Series wins. But the ’52 Topps Mantle is technically his first Topps card, and that fact has led it to reach Holy Grail status among collectors.

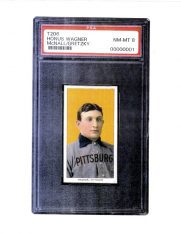

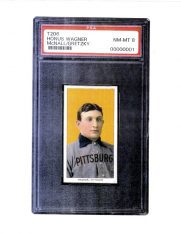

Honus Wagner, courtesy Ken Kendrick

Though high-end card collecting has attracted a wealthy clientele for decades—with the baseball card hobby becoming more of an investor’s game beginning in the mid-to-late ’80s—over the past three years or so, it’s transformed into a monthly dick-measuring contest for high-net-worth individuals. In May of 2018, for instance, “Vegas Dave” Oancea, a brash professional gambler and influencer, sold his one-of-a-kind Bowman Chrome rookie card of Los Angeles Angels superstar Mike Trout for more than $3.9 million at auction, also a record at the time. (Topps’ good fortune in ’52 allowed it to absorb Bowman in 1956.) The following year, a rare and decidedly busted 1909-11 T206 Honus Wagner card realized a hammer prize of $1.3 million (more on that card in a second). And the market hit a fever pitch in 2020, due in large part to the pandemic, during which millions of collectors were forced into lockdown, rekindling their interest in long dormant collections and sending the already-juiced seller’s market into a feeding frenzy (one market research firm values the current sports card market at nearly $14 billion, with it potentially ballooning to $100 million by 2027).

Just this past June, a pre–rookie card of Yankees great Babe Ruth raked in $6 million at auction, the current record price paid for a baseball card.

Poll the most dyed-in-the-wool collectors about whether the ’52 Topps Mantle is the most desirable card in the market today, though, and you might not reach a consensus. Long before Berger unwittingly solidified Topps’ legacy by disappearing that priceless hoard, the American Tobacco Company inserted a set of cards, the height of about a pointer finger, in its tobacco products between 1909-11, famously and inexplicably removing one from production early on, that of future Pittsburgh Pirates Hall of Famer Honus Wagner. Just under 60 are known to exist today, and as early as the 1930s, the Wagner was being listed with a value of $50 (roughly $800 in 2021 dollars). That hopscotched to $3,000 by 1978 and onward, until 1991, when hockey star Wayne Gretzky pooled resources with the owner of his then team, the Los Angeles Kings, and bought a Wagner for $451,000. Gretzky’s Wagner was then graded an 8 out of 10 by PSA and in 2011, after a number of subsequent sales, it was repurchased by Arizona Diamondbacks managing general partner Earl G. “Ken” Kendrick, Jr., for an unheard-of-at-the-time $2.8 million. Interestingly, two years later, one of the card’s original owners admitted to “trimming” it, or cutting its sides to make it appear more mint than it actually is. That fact has done nothing to deflate its value. A different copy, in a much lower, unshaved grade, recently went for $3.8 million.

Though Gough says he considered buying a Wagner, the Mantle, he believes, will prove a much better investment in the long run. “Ask anybody that you know that doesn’t collect who Honus Wagner is,” he says. “Nobody has a clue. So if you look at it from a collecting or value standpoint, it’s all about what do people know, what do people recognize. Nobody outside the hobby recognizes Honus Wagner, but they all recognize the Mantle card.”

That, and the Wagner just kind of “looks like shit,” says Gough.

The Mantle, on the other hand, is aesthetically pleasing, truly a work of art, something he’d be proud to hang on his wall—something he’s actually been mulling doing. “You look at Andy Warhol, say, the Marilyn print; it’s colorful…what’s the difference between that and the Mickey Mantle?” asks Gough.

Gough’s Mantle isn’t even the highest-graded or priced version. Three collectors own a pristine PSA 10, including the owner of that PSA 8 Wagner. Kendrick’s multimillion-dollar sports card collection is kept under lock and key in a vault in an unspecified location. Kendrick says that he’s fielded and turned down offers for both his Wagner and Mantle. (Heritage’s Ivy estimates each card’s value now north of the $20 million mark.) Despite owning both—as well as the highest-graded example of the ’51 Bowman Mantle for good measure—Kendrick, like Gough, has more reverence for the Topps card than the Wagner rarity. “You’re talking to one of those guys, who in the year 1952 as an 8-year-old, went down to the local five-and-dime and bought a quarter’s worth of cards regularly,” he says. “Five packs for a nickel a pack. I’d open them all up, stuff my mouth with five pieces of Topps’ bubblegum, and my buddies and I traded the cards.”

A boom … or a bubble?

With the average home value in Sunset Park around $550,000 and income at $70,000, it’s probably difficult for some to grasp that a piece of cardboard produced in a Bush Terminal factory in the 1950s could be worth as much as it is today. But the hits have kept on coming for Topps. That $4 million Mike Trout card was produced just 12 years ago. Similarly, a scarce Bowman Chrome card of Atlanta Braves star Ronald Acuña, Jr., which Topps produced only four years ago, sold at auction last summer for more than $230,000. Though Topps eventually outgrew its Brooklyn roots, moving its manufacturing hub to Duryea, Pennsylvania, in 1965, and its corporate offices to Manhattan in 1994, it never stopped producing baseball cards. It did remove gum from the packs in 1992.

The last time the card market waded into the billion-dollar belfry was in the late ’80s and early ’90s, when Topps had a lot more competition. During that first collecting renaissance, Topps’ Mantle emerged as a poster child for the hobby and a harbinger of things to come. “In the late ’80s, during the card boom, it was the one card that was a must-have for any serious collector,” says Clay Luraschi, vice president of product development at Topps. “People who had grown up during Mantle’s playing days had to have the card, and they wanted the Topps card because Topps was the company that had been chronicling baseball for the last 35-plus years.”

Thanks, however, to rampant overproduction by card manufacturers, Topps included, as well as a confluence of other factors such as the dawning of the internet age and the ensuing baseball strike of 1994-95, the card market’s bubble burst spectacularly in ’94, leaving myriad collectors, investors, and speculators with piles of worthless cardboard.

But the boom of these past few years has felt different, and Topps has come out the biggest winner. For one, the company doesn’t really have much competition in the market anymore—direct competitor Panini, for example, doesn’t share Topps’ exclusive Major League Baseball licensing rights, so its baseball cards feature logo-less players. And the market hasn’t shown any demonstrable signs of slowing down yet.

“You have a rising tide that lifts all boats in the market right now,” says Kendrick, a billionaire businessman in his own right. “Will the tide ebb? I believe that it will. Will it be like a bathtub where you take the plug out and all the water drains out? No, I don’t think it’ll do that. But I think the market will stabilize over some period of time, but right now, it’s hard to predict when that will be.”

The tsunami of interest has also translated into a rather tidy profit for Topps, which this year merged with a special purpose acquisition company (or SPAC) and has been given an early valuation of $1.3 billion. (The company plans to go public later this year.) And it couldn’t be happening at a more serendipitous moment for Topps. “The hobby is as healthy as it has ever been,” says Luraschi. “There are people of all ages involved, and we’re seeing a lot of kids. The industry is having a rebirth, and it’s incredible to watch and be a part of.”

You might also like