Source: Van Leeuwen Ice Cream

Van Leeuwen pioneered the artisanal ice cream boom. It’s finally ready to go big

Can it avoid the pitfalls that ensnared other brands?

On a recent fall weekday, just before the Omicron wave crashed into the tri-state area, dozens of people, mostly teenagers and their parents, lined up on an upper floor of the American Dream mall in East Rutherford, New Jersey, to go skiing.

The mall, a behemoth complex spanning millions of square feet, contains, among many other things, the country’s only indoor skiing slope, a DreamWorks-themed indoor water park, two miniature golf courses and a string of luxury retail shops.

Just steps from Big Snow, as the slope is called, a few families sit scattered across tables at the first New Jersey outpost of Van Leeuwen Ice Cream. The site is not far, as the crow flies, from Van Leeuwen’s physical starting point—a single New York City truck. But the mall is light years away from the world where the ice cream brand was born: late-aughts Brooklyn, the age of the “artisanal” food boom, during which young entrepreneurs and restaurateurs popularized a handmade, back-to-basics ethos using centuries-old techniques.

Founded in Greenpoint in 2008 by brothers Ben and Pete Van Leeuwen and Laura O’Neill (Ben and Laura were dating at the time, but no longer), the company quickly became popular for its minimalist but inventive flavors made from high-quality ingredients. Think Earl Grey Tea and Honeycomb—a concoction popular in Australia and New Zealand that pairs vanilla ice cream with small chunks of crunchy honey toffee—flavors that seem tame today but were far from a given 15 years ago. Van Leeuwen also made vegan ice cream that actually tasted good and became the envied standard bearer for tasty dairy-free alternatives. They spawned many competitors along the way, as arguably one of the most important pioneers of the artisanal ice cream movement, which is still ever expanding.

Today, the New Jersey mall location, flanked by an H Mart and a T-Mobile outlet, could be a sign of what’s to come. While Van Leeuwen has already started shipping across the country, dipped into the ice cream bar market and opened a series of scoop shops in California, Texas and Pennsylvania, it plans to get exponentially bigger: The goal is about 20 more cross-country shops in 2022 and 40 by 2024. A little closer to home, starting today you can stop by their new Park Slope location on Fifth Avenue.

Ice cream at scale

Ben Van Leeuwen is slightly flustered in a Zoom chat from the company’s Greenpoint factory—he’s trying to fix a mechanical issue that’s preventing the pint lids from sealing properly. But he still manages to explain why he isn’t worried about trading quality for quantity in the expansion.

“If you make a homemade tomato sauce at home, it will be virtually impossible to find something in the supermarket that is as good,” he says. The ingredients just don’t coalesce. “At an industrial scale, ice cream gets better. If we had $30 million to build a bigger, newer factory, the product would be even better, because we’d have better temperature control … so the faster you freeze it, the smaller the ice crystals are.”

But growth is hard. The tension between big goals and tight finances got a bit of a reprieve about four years ago, when the Van Leeuwens relaxed their grip on the company and allowed interested investors to start buying portions of it.

“Maybe if we’d put our heads down and worked harder and been scrappy for longer, we could have held on to more of the company, but it was just too stressful,” Ben says. “We just said it’s not worth it.”

The three founders are still majority owners, and with the new funds they were able to expand their staff, hiring a chief operating officer and a human resources manager. Their financial planning has been savvy: During the 2020 pandemic year, when sales went down about 65 percent, the company didn’t close a single shop, and Ben says not a single employee was laid off.

The biggest hiccup in their plans came last October, when the company was fined over $12,000 for not accepting cash payments, a practice that’s now illegal in New York City. Eater reported in November that in addition to not having paid the fine, Van Leeuwen was still not accepting cash at any of its several locations across the city.

The company has not responded to a request for comment on the topic.

From left: Laura O’Neill, Ben and Pete Van Leeuwen enjoy a scoop (Courtesy Van Leeuwen)

The canary in the ice cream coal mine

The cautionary tale about ice cream expansion is that of Ample Hills, the spunky Brooklyn brand with creative flavors that opened in 2011 to talk-of-the-town acclaim. Its first shop, on Vanderbilt Avenue in Prospect Heights, sold out of its entire supply in four days and had to temporarily shut down to restock. The legend of its tastiness grew from there. A sort of anti-Van Leeuwen, its flavors were stuffed with delicious chunks of cake and cookies (and came with humorous names like It Came From Gowanus, a reference to the polluted Gowanus Canal). As an Eater article famously declared: “There Are Two Kinds of People: Those Who Like Van Leeuwen, and Those Who Like Ample Hills.”

But over time, Ample Hills prioritized expansion—which included brand collaborations with Disney and building an enormous Red Hook factory that was not properly planned—that ultimately doomed its bottom line and led to bankruptcy and a sale to new ownership in 2020.

Brian Smith, who with his wife Jackie Cuscuna founded Ample Hills and now runs The Social ice cream shop on Washington Avenue, looked to Van Leeuwen, among others, as inspiration in his early ice cream-making days, even though their brands were wildly different. He says Ben’s approach to making ice cream at scale doesn’t hold true for every style—for example, Graeter’s, a nearly 150-year-old company in Ohio, still makes all of their product a few gallons at a time, even though they have expanded and now ship across the country. That’s because some of their flavors are full of chunky ingredients, which can get stuck in larger “continuous” freezers, as they’re called. Graeter’s has 50 or 60 small-batch freezers going at one time, says Smith, who researched their inner workings while planning Ample Hills. Some of it might also just come down to preference.

“Graeter’s said, ‘Hell no, we’re not going to change the way we make our ice cream as we grow, because it’s going to change how specific we are and how unique we are,” Smith says. “Everybody’s got a different identity.”

Van Leeuwen’s ice cream, which does occasionally feature cakes and cookies but is mostly of the smoother variety, is easier to put through continuous freezers—and therefore primed to be improved when scaled up.

“This will affect a Van Leeuwen less than an Ample Hills or Ben & Jerry’s or The Social, because their focus isn’t on wild and crazy mix-ins,” Smith says. “For what Van Leeuwen’s doing, Ben’s absolutely right.”

Ben, 38, is involved in just about every aspect of the business, bouncing from shareholder meetings to marketing department email threads to the factory floor to social media videos. Pete, 45, and Laura, 40, both live in Los Angeles now and visit Brooklyn on business trips multiple times per year.

In the middle of our Zoom, Ben jumps off to a different call to talk about quarterly revenues, but 45 minutes later, he’s back and happy to get back to talking details—covering everything from the melting points of different fats and nut butters (this lactose-intolerant reporter was especially interested in the science behind the vegan varieties) to the Sicilian village that he imports pistachios from to make one of his favorite flavors (it’s located a few miles from Mount Etna, an active volcano). He’s dressed in a plain white tee and talks at a slow and measured pace,

like a seasoned university professor.

“How have we survived and been able to grow and stay in business? Just obsessing over cost control,” he says. “The more I learned about business, the more I realized I know nothing. Every year or two, I look back and I’m like, ‘Oh my God, how could we have done that that way?’ What you learned seems so obvious.”

Christophe Marchand

Simple ingredients? ‘Kind of radical’

Ben traces the roots of what he calls his “really healthy fear” about money back to his childhood in Greenwich, Connecticut, a wealthy place where he says his family stood out for its financial struggles. His father, who immigrated to the U.S. at 9—and whose parents were Dutch Jews who escaped the Holocaust and lived for a time in Aruba and Jamaica—was an entrepreneur who founded several businesses, including an ad agency and an early software company that helped travel agents look up flights on the nascent internet.

In high school, needing a summer job, Ben saw an ad claiming that vendors could make hundreds of dollars a week selling Good Humor ice cream out of a truck. He jumped at the opportunity and hocked the brand’s famously kitschy products, the polar opposite of what would become Van Leeuwen’s signature: cookie ice cream sandwiches, bubblegum popsicles, pops in the shape of Spongebob Squarepants. He says that in his second summer of driving the truck, with help from his brother Pete, they made about $40,000.

With that money he took a nine-month pre-college trip to parts of Europe and Southeast Asia, where he was blown away by how seriously people treated the ingredients behind their food—and how accessible good ingredients were.

“In Italy, it’s normal to talk about where ingredients are from. You’re not a snob or a foodie,” he says. “Going into the equivalent of just a cheap, normal grocery store, they have, like, 35 different cheeses, and olive oils from 10 regions. But all really affordable.”

While at Skidmore College he worked at an artisanal bakery called Mrs. London’s, and his boss gave him the “Zingerman’s Guide to Good Eating,” a book on “how to choose” good ingredients, written by one of the founders of the famed Zingerman’s Deli in Ann Arbor. His interest in ingredients grew, and he learned from his bakery bosses that they used things like a special Celtic sea salt and flour from biodynamic wheat. When he saw a Mr. Softee truck drive by one day, he became obsessed with an idea that brought his journey full circle: making high-quality ice cream from really good basic ingredients.

In 2008, the Van Leeuwen founders, who all ended up living in Brooklyn at the time, raised $60,000 from family and friends, just enough to buy a used truck on eBay and find a factory upstate that would produce their first creations. They wrote their own press release and sent it around, earning buzzy writeups in The New York Times and New York Magazine. The truck hit the streets in June.

Food writer Hannah Howard, who was an undergrad at Columbia at the time and interning at Serious Eats, remembers the Van Leeuwen truck debut as a splashy event, the equivalent of an anticipated rock concert in the food world. The truck was bright yellow, with a logo in an elegant cursive font. Everything from the advertised flavors to the logo aesthetic were “sophisticated and interesting” to her, especially compared to what was booming on the Upper West Side where she was living—mainstream frozen yogurt chains, such as 16 Handles and Red Mango, what she called “all chemicals.”

“Van Leeuwen was kind of radical, because they were the opposite of that, they were just making something from milk, cream, eggs, sugar,” Howard says.

She trekked downtown with friends to SoHo, where the truck had finally found success—after numerous false starts in the Wall Street and Canal Street areas—and had to wait in a line to get what she came for.

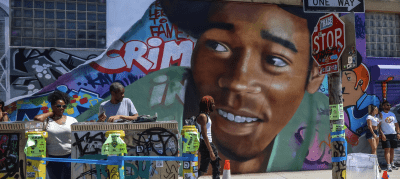

Early days. (Courtesy Van Leeuwen)

Death threats and slashed tires

The early buzz allowed them to open brick-and-mortar shops in Brooklyn, Manhattan and eventually Los Angeles. Then came the tough times that most small companies go through—and then some. A Mr. Softee employee named Tommy, who bragged about having served time for manslaughter, left voicemails in which he threatened to kill their families. A few years in, Ben did some math the day after Christmas and calculated that the company was going to be $200,000 in debt within days, so he found a loan for $250,000 at 37 percent interest. They all worked 12-hour days for years.

After they started serving coffee in their initial trucks, competitor coffee cart vendors started slashing their tires.

“We didn’t have as many connections and vendors then, so our mechanic was in Flushing and he could change tires. So at around 10 p.m., you know, on 25-degree nights in January, we’d be in the truck getting it towed to Flushing, we get home at 4 a.m. with the truck, and in the meantime, the generator would sometimes run out of gas, and the espresso machine would freeze, and the boiler would burst,” Ben recalls.

Ironically, as the competition increasingly mimics Van Leeuwen, Ben is driven to expand even further. Store shelves are all-out battlefields, and most people around the country don’t know the Van Leeuwen name. “Velocity,” or how fast one’s product gets bought from the shelves, is “everything” these days, Ben says.

“Early on, I was very naive, and I think we all thought, ‘let’s make an ice cream, let’s make the packaging pretty, sell it to a grocery store, and people will buy it.’ And actually, when we started, it kind of was like that, because there was so little competition,” he says. “But now we can go into Whole Foods, or any store of that size in New York City, or major markets, you’ll probably count like 30 to 50 ice cream brands, you know, many of which are around the same price point we are in and are at the very least advertising the same quality and attributes that we have.”

Just a handful of competitors who have gained ground in recent years include Coolhaus in Los Angeles (which boasts on its site about starting as “a broken-down truck” at a music festival); McConnell’s in Santa Barbara (which revamped its half-a-century-old business in 2013); Jeni’s in Columbus (which claims it started the artisanal ice cream boom when it opened in 2002); and Salt & Straw in Portland (which hasn’t become a Whole Foods regular yet but is threatening to gain a New York foothold). Several others in Brooklyn, including Blue Marble and Malai, similarly focus their narratives on quality globally sourced ingredients.

One big way Van Leeuwen has differentiated over time is its wealth of vegan options, says The Social’s Brian Smith. Most brands only offer a few dairy-free options, he says, something he is looking to expand on at The Social.

“They’ve done such a beautiful job with it … the creativity of the vegan flavors has been definitely a model and an inspiration,” Smith says.

While most stick to one main dairy alternative in their dairy-free recipes, Van Leeuwen uses both cashew milk and coconut cream for a thicker product. They’ve also launched an entire line of flavors with an oat milk base. Sticking to his chemistry, Ben says their vegan products are about 45 percent “solids,” the rest water, while most competitors’ products are around 35 percent solids. The more water, the less body and taste.

Despite all this expansion, Ben says the company has a Brooklyn spirit at its core. In the summer, a local baker set up on a bench in Greenpoint’s McGolrick Park, near Ben’s apartment, selling bread, chocolate chip cookies, caramel chocolate bars and lemon pound cake. Ben says the products were so good that he became inspired all over again.

“It’s so cool that someone cared that much to make something that is so delicious,” he says. “That’s the romantic idea of this. We’re becoming a bigger business, but we want to make products like that, at scale, and make them widely available and super price accessible.”

“Ice cream,” he adds, “lends itself really well to that.”

This is an updated version of an article that first appeared in the winter/spring 2022 issue of Brooklyn Magazine. That version neglected to mention the fines for violating the city’s cashless ban. Click here to subscribe today.

You might also like