Courtesy Crown Finish Caves

A private tour through the cheese caves of Crown Heights

In Crown Finish Caves on Bergen Street, 26,000 pounds of cheese is aging right under your nose

Thirty feet below Bergen Street in Crown Heights, there is a network of tunnels. Inside those tunnels are 26,000 pounds of cheese, gradually aging. The caves themselves are home to Crown Finish Caves, owned by Benton Brown and Susan Boyle, and they have been off limits to the public since the onset of the pandemic.

But lovers of artisanal cheese can now sample their fine art of affinage, or cheese aging, above ground every Friday, from 3 to 6 p.m.

Down there, “the cheese is alive and always growing, so we need to keep the conditions as clean as possible,” says Brown.

Up here on the ground, the results are palatable, occasionally pungent and always pleasing.

Cavernous

Aging cheese in an underground brewery

Crown Finish Caves is a licensed dairy plant that practices affinage, the art and science of aging cheese. Housed in a repurposed 1850s facility once used for fermenting beer, Crown Finish exploits the vaulted brick lagering tunnels that also happen to provide the perfect environment for this centuries-old cheesy craft. These subterranean cellars have remained at the same cool 50 degrees since they were home to the Nassau Brewery, over a century-and-a-half ago.

Crown Finish Caves does not make the cheese, though; rather, they buy fresh, under-ripe cheeses (too young for human consumption) from seven approved suppliers across the United States and from as far afield as Italy and Spain, all notable for the high quality of their milk—be it from cows, sheep or goats.

“Cheese is a lot like people,” says Brown. “They come into our lives as little babies and we take care of them and do our best to guide them. And when they are ready, we put them out into the world.”

Inside the caves

Once upon a time before Covid, Brown gave tours of the caves by appointment and occasionally hosted concerts there. But these days only his staff of two is allowed downstairs.

Brown consented to give Brooklyn Magazine a tour, before which we donned a hairnet, a lab coat and protective booties, all to ensure that no germs would be carried into the cheese sanctuary.

Down 30 feet of steps, there it was: 26,000 pounds of cheeses resting on shelves in various stages of aging. As we moved from wheel to wheel, Brown explained that the cave aging process depends on a tightly-controlled, microbial ecosystem, requiring constant vigilance. Surprisingly, there isn’t much odor. It is imperative that there is absolutely no contamination.

“This is a very serious issue,” says Brown. “As a small company, we spend tens of thousands of dollars every year on lab work, constantly monitoring the environment and testing the product.”

Each day Crown Finish Caves’ staffers can be found examining the babies, monitoring their moisture and determining when they are ripe enough to be sent out into the world.

An apprenticeship in France

Long before Brown became an affineur, he was a sculptor, an artist of a different flavor.

“Getting out of the art world, which I did not like, and moving into the creative food world of farmers versus dealers is what makes me happy,” he says.

Brown and his wife, Susan Boyle, bought the building in 2001 and converted the floors above ground into art studios which they rent out. It was when they realized that the caves below would be perfect for cheese aging that Brown took up the calling. Knowing that he knew next to nothing about the cheese aging process, he traveled to Mons Fromages, a cheese aging facility in France, where he spent a few weeks as an apprentice, learning to master the art of ripening. Like musicians who can identify when a note is a little sharp or flat, cheesemakers can recognize subtleties in flavor levels and understand how to improve their products. “It was a sensory education,” says Brown.

He chose Mons Fromages not only for its similarity to Crown Finish—instead of old lager tunnels, there they age cheese in a train tunnel—but also to learn about their business model, which, like Crown Finish, is receiving green cheese from producers and aging and selling it.

“I handled some of the cheeses to see how they worked with it, the tools they used, how long things aged, tasting, smelling, touching, looking at their aging equipment, talking about the pros and cons of different equipment,” says Brown.

He brought this new knowledge back to Brooklyn, where Crown Finish received its New York dairy plant license in 2014. Today, some cheeses are aged for as little as two weeks ( the softer cheeses), some as long as a year (as with the 30-pound Alpine-style wheels). Some are washed every other day; some are inoculated with ripening cultures, while others are deliberately aged as naturally as possible.

From one ingredient, many varieties

To make cheese, one requires only a single primary raw material, milk. Yet, out of that simplicity arises a mind-boggling diversity of flavors.

Take Crown Finish’s “Gatekeeper,” a soft ripened, triple crème that is aged just 15 days and has won awards.

Another popular variety is “Washed Bufarolo” from Bergamo, Italy. Aged between six to eight weeks, this Taleggio-style cheese is washed in beer and finished with a gentle bloom of ambient flora to give it a sweet and mushroomy tang. “An excellent choice for buffalo milk fans looking to go deeper than mozzarella,” says Brown.

Named for William Bunker Tubby, a prominent turn-of-the-century architect, the “Tubby” is a 30 pound Alpine-style cheese that is traditionally handmade in a copper vat and washed in brine for a year, the time it takes to encourage the development of microflora. Brown describes Tubby rind as crunchy peanut butter “with an aroma that will whisk you away with notes of pineapple and tropical fruits.”

Once the cheeses are ready, Crown Finish wholesales them to restaurants and distributors and retails them through their online store.

Or you can sample them for yourself at the Friday tastings. Along with the cheese—try the Raclette-style, melted over potato—there is usually a local guest purveyor with samples of pâtes, kombucha, gougères and more.

“For me it was the taste of France,” says Pat Mainardi, a local art historian who goes every week for the tasting. “Fabulous cheese I couldn’t believe I was getting in Brooklyn.”

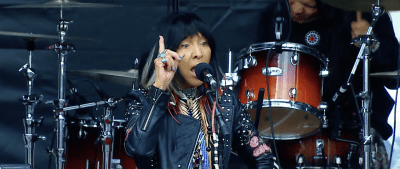

The Friday pop-up (courtesy Crown Finish Caves)

You might also like