Staubitz Market by Geoff LMV, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Remembering John McFadden, Sr., of Staubitz Market

The beloved butcher and neighborhood pillar passed away last month, leaving a hole in the Court Street community

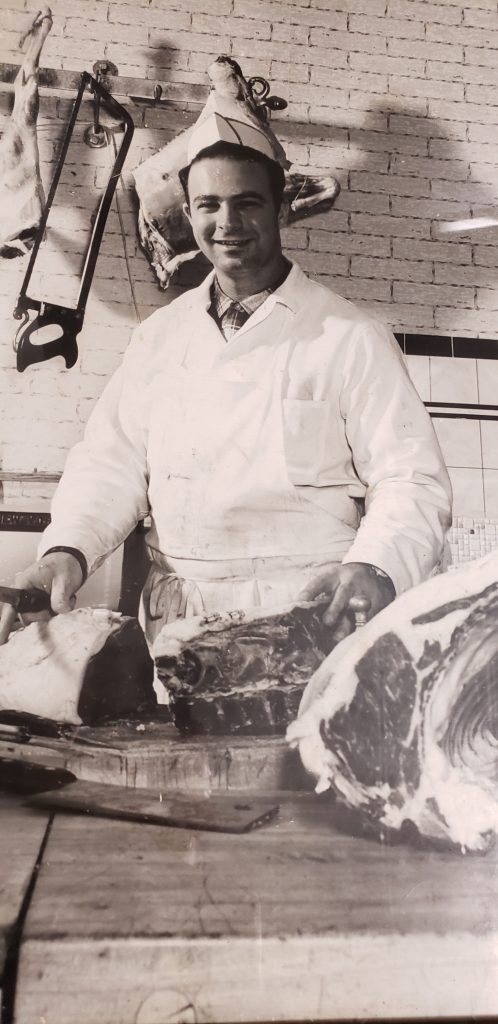

John McFadden, Sr. (1936-2022) at the counter in the 1960s (Courtesy John McFadden, Jr.)

Among the greatest pleasures of living in brownstone Brooklyn is knowing the people who do all the jobs that make daily life possible. Joanny at D’Amico grinds my coffee. Merrick at KC Arts finds exactly the right supplies for my kids’ craft projects. And until recently, John R. McFadden at Staubitz Market butchered my meat. On October 9, after 67 years at the store — a run as long and storied as the Dodgers’ in Brooklyn — McFadden died, leaving a hole in the neighborhood’s heart.

If you aren’t familiar with Staubitz, you probably don’t cook your own food.

This butcher shop, located on Court Street in the center of what is now known as the unfortunate real estate broker neologism BOCOCA (for the nexus of Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens) opened its doors in 1917, almost two decades before McFadden was born. In 1955, after finishing formal training as a butcher at what was then the city’s Food Trades Vocational High School, McFadden, then 19 years-old, began working at Staubitz; 12 years later, he became the owner.

In every year since, McFadden, always dressed in an apron with his white paper butcher’s hat, took great care to preserve traditional elements of the store. Sure, we food-obsessed city dwellers want to taste the newest artisanal ketchup, we want to try the latest imported vinegar; why not? But we also want to hang on to old, good things that don’t need improvement — like a butcher shop with sawdust on the floor, house accounts, and a staff with seriously legit knife skills. Staubitz is that place, and McFadden kept it that way.

I’ve been shopping at Staubitz for 20 years, which means McFadden took my orders when I cooked only for two people and ate meat just once or twice a week. When I found myself needing to feed a family of five — and occasionally, several others — he pointed me to flank steak and ground-up pounds of beef and turkey, but only after first bestowing lollipops on my toddlers and providing me with a much-needed brief reprieve.

He talked me through my first crown roast of pork, and, on special occasions, sold me the choicest ribeyes.

But the thing he did best, the thing that makes Brooklyn great, is that he hired a group of people who maybe didn’t have a lot of other options and gave them a chance, supplying them with the skills and a pathway that could ultimately provide for their well-being.

In an era when virtue signaling is sometimes valued more highly than deeds, it’s easy to overlook how difficult — and important — it is to take actual responsibility for others. But that’s what McFadden did: he gave a diverse group of Brooklynites jobs and kept them working for years, and in some cases decades, allowing them to provide for themselves and their families. And all along the way he prepared his son to take over.

That stability is hard to come by. For me, as a customer, it meant that year, after year, decade after decade, I could go to the store and count on seeing the same faces behind the counter and know everyone there could answer my questions and provide professional service. If it wasn’t John Sr. helping me, it was John Jr., or someone else who had been there 15, 20, or even 30 years. Recently I stopped by the store and was helped by Frank Ferrigno, a butcher who went to work for McFadden more than 40 years ago, and, with the skills McFadden taught him, opened a series of shops around the city; recently he returned to help out.

For Ferrigno, McFadden wasn’t just a boss, or even a mentor. “He was like a father to me,” Ferrigno says. Other employees felt the same way; one even saw fit to tattoo McFadden’s face on his left calf.

John Jr. who started working at the store when he was 11, always understood that the family business was not only taking care of customers but being a bulwark of stability. “Even during tough times when others would have started cutting employees, he kept them on,” John Jr. tells me. “He felt very responsible for them: one guy has got 5 kids, another guy has 3 kids. He felt it was important.”

McFadden’s death will be grieved for a long time by his loyal customers, but some of us find comfort in the solidity of what he built. Today, just as when McFadden Senior became owner in 1967, antique light fixtures still illuminate the store. Daphne the cat still guards the meat case. McFadden’s hand-picked staff of skilled employees still fulfills my orders.

John Jr., who is 55 and already has nearly four decades at Staubitz, doesn’t plan to change much. “That’s how I learned the business and that’s how I intend to keep it.”

You might also like