Chancellor King, center, flanked by his father and uncles (Photo illustration by Christophe Marchand)

King’s County: SUNY’s new chancellor comes from a line of Brooklyn educators

Former Secretary of Education John B. King Jr. is settling into his Albany digs, thanks in no small part to his trailblazing father and uncles

“Did you hear the cast story?” asks SUNY Chancellor John B. King Jr. It’s the same story he told Congress during his confirmation as President Barack Obama’s secretary of education. But he’s more than happy to tell it again.

King’s father, not yet old enough to vote, was beginning a pioneering career in education in the late 1920s. He arrived at P.S. 26 in Bed-Stuy with a cast on his right wrist from an accident during pickup basketball with his famous brother Dolly (more on him later). The principal walked in.

“You can’t teach with that on.”

King insisted he could. The principal was adamant he could not teach with a cast. Defiant, King Sr. pounded his broken right wrist on the classroom lectern. The cast shattered. He washed his hands, disposed of the debris, and calmly declared himself ready to teach. The principal obliged. The students walked in, none the wiser, and the young grammar school teacher began his new path.

“I often think about that story … it drives me,” says King Jr. of his dad. “It shows the importance of education and showing up. There’s a lot in my family story that is instructive about the possibility of progress in America.”

As it was, the cast story is one of very few memories imprinted on King Jr. by his father, who died when his son was just 12. John B. King Sr., the borough of Brooklyn’s first Black principal, was so highly regarded that, later in his career, he was appointed to the superintendent’s office and given a testimonial dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria.

Like his father, King Jr. is two things at his core: a New Yorker and an educator. After a brief Maryland gubernatorial run, he was appointed SUNY chancellor in December 2022. He took office in January.

“[King] wanted to work in a setting that serves lots of folks instead of just the elite,” says President Obama’s first education secretary, Arne Duncan, under whom King served as deputy before succeeding.

King’s cousin, retired marketing executive, Haldane King Jr. put it this way: “As chancellor, he’s home.”

“So much of my identity is tied to growing up in Brooklyn,” King Jr. explains. “It defined my time growing up.” He attended P.S. 276 in Canarsie and Mark Twain Junior High School in Coney Island, and after a rough patch, Harvard. From there he would attend Yale Law School and receive a doctorate in educational administrative practice at Teachers College at Columbia University.

“His deep New York roots make him an ideal leader,” Governor Kathy Hochul commented via email.

John B. King Sr.

Teaching in the blood

Gov. Hochul’s description of King Jr. evokes his own father’s days in the classroom. In 1960, a colleague of the senior King’s told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “He is an inspiring leader.” It is in many ways a bittersweet parallel: The loss of his father defined the younger King’s formative years. His mother had died four years before his father, who was already suffering from dementia.

“One of my father’s students wanted to pay his respects [at his wake] because my father impacted him as a teacher. That always stuck with me,” King recalls. “He really believed that education was the best path forward to strengthen our democracy.”

King’s father, the oldest of seven children, graduated from Boys’ High School at just 15 in 1924 and planned to become a surgeon. In 1926, his own father died. As the story goes, destiny intervened on the old Gates Avenue El, now the J train. John King Sr. glanced over the shoulder of a young woman holding a teacher’s exam. He answered the questions to himself as the El rattled over the Williamsburg Bridge.

“By the time the train had reached Canal Street, I had answered every question,” recalled King Sr. in 1951. “Getting off the train, I asked myself: Why not take the next examination … teach a few years … then medical school. That’s how it happened.” At 17, King Sr. enrolled at Maxwell Teachers College and was in the classroom, by 1928, at 19. “I fell so in love with teaching I just never gave surgery another thought,” the elder King added. (He still became a doctor, after earning his Ph.D. from NYU.)

When John King Sr. was included in an out-of-print 1970 anthology called “Negroes of Achievement in Modern America” — alongside Black icons including Martin Luther King Jr. and Thurgood Marshall — he asked the author: “Why do you want to write about me? You should be writing about a great man, Dolly.”

With the death of their father, King Sr. and his brother Dolly were charged with raising their brother Haldane while their mother worked nights. “John and Dolly and Hal, you’re the selected ones,” she would tell them. “You’ve got to get this done.”

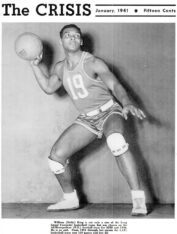

In those days, college basketball ruled New York. Manhattan had City College. Brooklyn had Long Island University. Dolly King put LIU on the map — in hoops first and foremost, but also in football and baseball.

Dolly attained mythological status on Thanksgiving Day, 1939. First, he brought the Ebbets Field crowd of 7,500 to its feet with a 54-yard touchdown catch while playing offensive and defensive end for an entire game. Later that day, Dolly changed his uniform and played in the student-alumni basketball game at the LIU gym in Downtown Brooklyn. Dolly then led LIU to the 1939 National Invitation Tournament title at Madison Square Garden.

King, who played baseball in the Negro Leagues, signed with the Rochester Royals in 1946 — then a National Basketball League franchise, now the Sacramento Kings — making him among the first players to break the color barrier.

“Dolly was able to overcome tremendous discrimination and hostility to pursue excellence in athletics,” King Jr. says of his uncle, whose life-sized visage hangs in the Barclays Center, home of the Brooklyn Nets. “Then he became a coach and tried to contribute to the development of other young men. I think it’s a really powerful example.”

Paying it forward, paying it back

After his own father died, King Jr. lived with his 24-year-old brother, who was ill-equipped to raise a child. Shipped off to school, he would be expelled from Philip’s Academy in Andover. From there, he landed back on his uncle’s doorstep, jaded, angry, and in need of guidance. Haldane, whose own brothers John Sr. and Dolly had filled a paternal void, paid it forward to his orphaned nephew.

“His example as someone who persevered through incredible adversity helped me to find direction and purpose,” King Jr. explains. “That was a crucial period. I struggled a lot with the rules, with adults, and with authority. My uncle and Aunt Jane ran a tight ship. A lot of structure. I needed that. We had a lot of conversations about my future.”

Chief among the wisdom Haldane, a Tuskegee Airman, imparted was that you can’t control what happened in your past, but you can decide what sort of man you want to be. Move forward from there.

“I remember that conversation so clearly,” says King Jr.. “It was really powerful.” His uncle’s discipline would ultimately propel King to the halls of power, but he never forgot where he is from.

John B. King Jr. (Courtesy the U.S. Dept. of Education)

A matter of policy

One of the primary reasons President Obama asked King Jr. to serve as deputy education secretary under Arnie Duncan, who he would eventually succeed, was his work as New York State Education Commissioner, where he developed a program to combat school inequality through diversity grants. An initial pilot program was implemented in Fort Greene.

“That’s the fight of his life; that’s who he is,” says Duncan. “We talked very openly and honestly about how important teachers were in his life and how his family situation was extraordinarily unstable. I wanted someone who would fight for kids for the right reasons and share my values. I didn’t know anybody better than John King. President Obama thought he was the right man.”

While at the White House, King Jr. helped President Obama implement My Brother’s Keeper, with the express purpose of helping students not dissimilar from King.

“There are some who want to hide the struggles our democracy has experienced, who believe we shouldn’t talk about the reality of racism,” says King Jr. “We’re going to build towards a more just society by making sure that all young people have a sense both of our progress and our struggles.”

That sentiment is another echo of something else his father once said. The elder King, who started Operation Reclaim to recruit fired Southern teachers who supported integrated schools, wrote a month before Jackie Robinson’s Brooklyn debut:

“Parent and teacher make education a combined effort to develop a new generation of people who can and will function as first-class citizens in a democracy. Since public schools serve as the bulwark of democracy, we must look for opportunities to strengthen the bond between schools and the community.”

King Jr. is keenly aware of the parallels between his story and that of his father before him.

“I don’t have words to describe how emotional it is to see so many echoes of my father’s career in my life,” he says. “It happened so organically. My career ended up following a similar trajectory. The things I’ve focused my work on so closely parallel what he focused on. It’s fascinating.”

You might also like