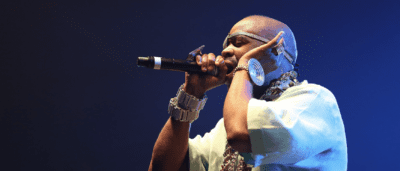

Ouigi Theodore at Brooklyn Circus (Photo by Kadeem Olijah)

Meet the ringmaster of the Brooklyn Circus

Apparel brand founder Ouigi Theodore discusses his approach to fostering a ‘global village’ — and his 100-year plan

Being from Brooklyn leaves a birthmark on your soul. Ouigi Theodore, founder of the refined urban apparel brand Brooklyn Circus, built his brand to honor the diverse walks of life that make Brooklyn uniquely Brooklyn.

Since 2006, the brand has produced a range of apparel that plays with the tropes of urban fashion out of its Crown Heights headquarters. In April, Theodore brought that Brooklyn state of mind to Manhattan, with a new shop on Canal Street. After capturing the attention of audiences both locally and internationally, including a recent collaboration with Lee Jeans, Theodore is ready to keep evolving and leaning into what he calls “the global village.”

Acutely aware that his rapidly gentrifying native Crown Heights was built by immigrants, marginalized communities and creatives from an array of diverse backgrounds, Theodore showcases their legacy through his history-informed designs. The Brooklyn Circus, both a clothing brand and inclusive space for all, is building upon those who came before him, in hopes of continuing to support the next generation.

Brooklyn Magazine connected with Theodore to discuss his fascination with history, his design process, and how he aims to circulate the Brooklyn state of mind all over the world. Excerpts:

(Photo by Kadeem Olijah)

How does your background inform your designs?

I was very involved in the sneaker business and the nightlife business, which intersected with design and culture. I really wanted to venture deeper into designing for others. We were some of the first people that brought hip-hop and reggae into the same room in Manhattan. Because before that, it was hip-hop in Manhattan and reggae in Brooklyn. After that, I decided I wanted to leave nightlife. I went to a trade show to see what other people were doing, and that gave me a lot of perspective. I took a friend up on an offer to use the front part of what was my office as a clothing store. So I started traveling, buying sneakers from elsewhere and bringing them here, maxing out credit cards and flipping sneakers. Sometimes people still think it’s a strange thing that we’d buy sneakers and resell them. But that’s really where I started.

Why Brooklyn?

I’m from Brooklyn — originally from Haiti. And there’s something very similar in parallel to Brooklyn. Parts of Brooklyn sometimes remind me of Port au Prince. I’ve always been a Brooklyn guy. Even when I ventured off to college, people would see it in my style. People would see it in the way that I moved. So I thought Brooklyn was an important place for us to start. And at the time, it was what we could afford. We ultimately went into business on a side street with this whole concept of “Come and find us,” you know, “Build it and they will come.” The Brooklyn opportunity was such that it served two purposes. It was one, an office because I was still freelance designing. And it was also an opportunity to meet folks and walk in and build relationships with them. From my early trips to Japan, I realized the appeal of some of these boutiques was that discovery factor. For me, growing up going to high school in Brooklyn, there was a big polo era. It was fun for us to venture outside of New York City to go find certain classic polo items.

You mentioned your personal upbringing, which influences what you create. But the brand is also really heavily shaped by its setting. How has Brooklyn influenced your designs?

It’s really about a Brooklyn state of mind, right? I had guys tell me in the beginning that with Brooklyn in the name, they didn’t know how much I was going to grow outside of Brooklyn. But I think that’s actually the wrong way to look at it. Because Brooklyn is a state of mind. New York is a state of mind. People come to New York and claim New York on year three, four or five. It doesn’t mean that they don’t love where they come from. You become a New Yorker or you become a Brooklynite. And being a Brooklynite is not because you’re just necessarily living in Brooklyn. For us, it was more about someone that appreciated the point of difference that Brooklyn brought to the conversation. That’s what the foundation was. So when I design, I’m normally thinking in that way. To me, a Brooklyn state of mind is a Brooklyn brownstone, a Brooklyn scene in a Spike Lee movie, or Brooklyn sports teams. When I design, I want to dive into this deeper history. And because of that, we’ve managed to attract crowds from as far as London, Paris, South Africa, Mozambique and more because they align with our way of thinking and it ultimately created this global village tribe.

There are definitely certain cultural touchpoints that many communities have consumed and it really does expand Brooklyn’s culture well beyond the city. It makes you realize that it doesn’t have to be this insular experience.

I grew up in Crown Heights. I was literally a block and a half away from the Brooklyn Museum, the Brooklyn Botanical Garden, the Brooklyn Public Library and Prospect Park. And when you step foot in all of those institutions, you’re meeting people from all over the world. You’re connecting to Caribbean communities, Russian communities and Asian communities. We don’t want to limit ourselves; we want everyone to be able to resonate with it.

How would you describe The Brooklyn Circus family or community in three words?

A global village.

How does your background in sneakers play into your current design process?

We like to label it as “tailored casual.” It’s an evolution of what is urban. It’s refining urban image, and its style and character. It’s, again, rooted in this global village. It’s Black Ivy, and by that, we mean that we stand on the shoulders of educators. We stand on the shoulders of campuses that were built to empower marginalized people. We stand on the shoulders of immigrants who ventured into Brooklyn, into Queens, into Manhattan, into other places across the globe, and across the world. Immigrants who came and brought their stories to these foreign places made their mark and ultimately made those places home. Still rooted in their upbringing, they also created a second home for themselves. I respect prep apparel, but we are attached to it in the sense that hip-hop is rooted in and attached to jazz music. You understand the connection and the drumbeats and the foundation. But hip-hop is hip-hop. So yes, we’ve pulled inspiration, and we’re inspired by prep and the collegiate lifestyle. But I think The Brooklyn Circus has clearly shaped and carved its own lane. Most importantly, the conversation we want to spur is always within this global village. It has to make sense to us as global villagers, meaning we are thinking globally.

What would be some of the garments that you would want to highlight from the past few months? What do you see people gravitating toward?

I would definitely say our varsity jacket has always been at the center of the conversation. In the Canal space, we’re playing a lot with linen. We’re playing a lot with deconstructing garments and reconstructing them. We have the Ragabond, which is a super loose linen patchwork pant — that has been a hit for us. And we’re diving into the women’s space with what we call our dress shirt, which is an oversized shirt that can also be styled as a dress. And I say it’s womenswear, but it’s really for everyone. I’m so excited about doing more of that kind of stuff and excited to play with pleating because it gives us the chance to say more and really dive into the layers of our creative process. So we’re definitely excited about bridging the gap between our Black Ivy roots and our collegiate roots, and moving into a space where we can continue to evolve 10, 15 years down the line.

It has to be really cool to see the different ways that people interpret all of your pieces.

There are so many creative people who stop into the stores. When someone takes a shirt and they flip it a certain way, and you’re like, “Oh, I never thought about it that way.” That’s what creativity is. And we’re all creative, right? No matter what profession we’re in, it’s just a matter of us tapping into that.

You recently collaborated with Lee Jeans for a collection that was inspired by America’s Black cowboys throughout history. In what other ways does the brand pay homage to history and what does legacy mean to you?

Stories are important to the fabric of human touch and human connection, right? And as interesting as we are as a group of people at The Brooklyn Circus, we find it even more interesting to be able to go and speak for others and tell their stories using our platform. To speak for others whose stories were buried in history or whose stories are still currently buried in it. We are here to pull stories from the past and bring them forward with us. We are here to add to the fabric of America. So storytelling is very important to us. And then also knowing how to archive because archiving is important.

I find it really meaningful to find brands or creators who have a platform that they use to tell stories that everyone doesn’t know the ending to, like telling stories of marginalized communities that maybe didn’t receive that type of visibility before. I think the Lee collection was a great demonstration of that.

When you get a platform, are you just going to use it up talking about yourself? That says a lot about a person.

I know that The Brooklyn Circus is a lot more than just the clothes. You have a 100-year plan. You have community activations and events where anyone is welcome and I would love to hear more about all of that.

I created the 100-year plan years ago because I realized that in business and all of the things that I studied, it was always about, “What’s your five-year plan?” And five years seemed like a long time because even when we were signing the first lease, the yearly options seemed like forever. I thought one year was just a whole lot of time, right? Yeah. But then when you’re trying to build something of value, it takes a long time and you value time more. So I decided, no more five-year plan, no more 10-year plan. What’s the 100-year plan? I decided that we wanted to add to the fabric of what menswear and American fashion was and how it appeared to the world. I am approaching American history from my perspective, my voice, which is the voice of an immigrant, of Black and Brown folks, and I want us to continue to thrive. I also want our way of dressing to evolve and continue to thrive. Yes, I’m attached to certain pairs of jeans. Yes, I’m attached to the varsity jacket. But if we continue to evolve those silhouettes and details, then we can appear in the world as chic as our Japanese, Italian, and French brothers out there.

What are the specifics of the plan, then? And your plans to continue expanding the brand outside of Brooklyn?

We want to work on a library, for sure. The Canal Street store is laid out as a gallery for us to be able to do shows and events. We’re trying our best to hire young creatives or young students so that we can grow with them. The library would be a space where you can come in and take out books and enjoy the space. And I want it to be accessible to everyone. I want folks to be able to travel across the country or across the world and step into The Brooklyn Circus world and think, “This feels like home.” I ultimately want to elevate the experience in my community.

The Brooklyn Circus is located at 150 Nevis Street in Brooklyn and 361 Canal Street in Manhattan.

You might also like