Courtesy of The Billion Oyster Project

100 million oysters and counting

Behind The Billion Oyster Project's efforts to restore New York City's waterways, one shell at a time

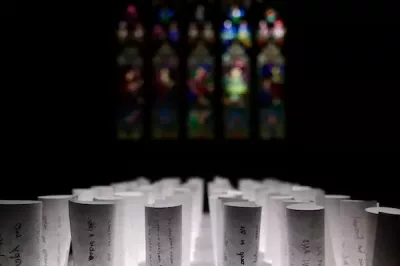

The fundraising gala at the Navy Yard (courtesy The Billion Oyster Project)

Last Friday, The Billion Oyster Project held a pearl of a party, a blowout fundraising bash at the Brooklyn Navy Yard with the goal of raising awareness (and, not incidentally, a lot of cash) to clean up New York’s polluted waterways and restore their marine habitats — one oyster at a time.

“Everyone who is excited about farming and aquaculture, who thinks about what happens when an oyster goes from farm to table, and then that next special step which is the recycling and turning them into oyster reefs, comes to celebrate,” says the project’s Katie Mosher.

Some of them came to the tune of $500 a plate. But there were no fancy suits, no floor-length gowns. The dress code was all about practicality: jeans, cozy sweaters, sturdy boots and trusty sneakers. Perfectly suited for slurping.

Oyster farmers from California to Washington, from New Orleans to Maine, were on hand to offer up samples of these aphrodisiac appetizers. In addition to gorging on all-you-can-eat oysters (none from New York Harbor, though — those aren’t yet fit for eating), guests mingled with chefs from the 72 restaurants that partner with The Billion Oyster Project, including local eateries Pips, French Louie and Lighthouse BK.

Caroline Schiff, the executive pastry chef at Gage & Tollner, delighted with one standout offering, a playful twist on oysters and pearls: little white chocolate truffles served in a real oyster shell.

New York’s oyster history in a half-shell

When Henry Hudson sailed into New York Harbor 415 years ago, the river that now bears his name held a prestigious position as one of the world’s foremost oyster hubs, containing more than 350 miles of oyster reefs in the harbor, more than half the oyster supply in the world.

By the 1800s, oysters were New York’s most notable nosh, so cheap and plentiful that they were sold on city streets like hot dogs are today. They adorned the menus of quaint saloons and found their way onto floating barges. New Yorkers savored these briny delights in a myriad of culinary forms: raw, roasted, pickled, fried or harmoniously integrated into chowders, sauces and stews. The Big Apple was more accurately one succulent oyster on the half shell.

But thanks to a cocktail of overfishing and untreated sewage, New York’s thriving oyster population began dying off. By 1927, the oysters were too polluted to eat, and the last oyster bed was closed by the city. Bye-bye, bivalves.

A 100 million milestone

Today, a glimmer of hope filters through the depths of this aqueous tale. The Billion Oyster Project, a nonprofit organization based on Governors Island, works in collaboration with New York City communities to restore oyster reefs to New York’s polluted waterway. The goal, as its name suggests, is an audacious one: to restore a billion oysters to New York’s harbor by 2035.

With the help of students, volunteers and partners, the organization says it has already reintroduced 100 million oysters to the harbor since its founding in 2014.

Each oyster slurped down leaves behind a shell, and recycling those shells instead of sending them to a landfill helps rebuild oyster reefs that offer a myriad of ecological benefits — from the creation of habitats for other marine life to protecting the city from storm surges.

“Not only do oysters help filter the water,” says Mosher, “but, if you were to reverse that and say we need to clean the water in order for oysters to be healthier so all the species that use oyster reefs can thrive, there’s no reason we should still have sewage flooding into our waterways every time it rains.”

A single oyster, she points out, can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day.

To accomplish all of this, the organization engages the local community in its shell-collection program. Once a week the collection team picks up shells from its 72 partner restaurants and transports them from a depot in Greenpoint to Governors Island where they are put through a long process to restore oyster reefs that help protect the city from storm surges, among other benefits.

“Nobody’s really done this before,” Kevin Quinn, senior vice president of design and construction for Hudson River Park, said in a 2021 interview with the New York Times. “It’s exciting.”

So exciting that royalty has gotten involved: The significance of The Billion Oyster Project reached a global stage during Climate Week earlier this month when Britain’s Prince William suited up with waders and gloves and, says Mosher, “dove right into the effort alongside our team. He got right in there with the students, assisted in the measurement of oysters that they brought out of the water, and had a great time.”

Prince William with The Billion Oyster Project (courtesy of the project)

The project works with students of all ages throughout the city, from kindergarten to graduate school, though not all of them get to wade with royalty. “We write curricula, we are in the classrooms, we’re teaching teachers how to bring students to the field so they can learn about oysters the same way they would learn about any other subject,” says Mosher.

“When I first saw an oyster I thought, ‘This is just a shell. What can this do?’” Helen Espinal, a sixth grader at Middle School 5o, said in an interview with Scholastic’s ScienceWorld last March. “And then, the more you learn about it, the more you see how much power this little animal has.”

Volunteer students wading in the water (courtesy The Billion Oyster Project)

You might also like