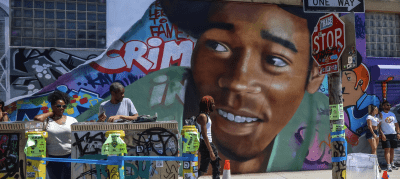

Photo illustration by Johansen Peralta

Karen Blondel: ‘The Fearless Princess of Red Hook’

The housing advocate and environmental activist (and David Prize winner) discusses her life as an 'undercover boss'

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

Chances are, if you live and work in Red Hook — if you care about the community and its well-being — you’ve come across Karen Blondel, president of the Red Hook West Houses Residents Association and longtime climate activist. Last month, Blondel received a new, more citywide form of recognition when she was one of five New Yorkers presented with the annual “David Prize.” A sort of annual MacArthur Genius grant for New York residents, the David Prize awards a no-strings-attached gift of $200,000 to locals doing on-the-ground work to rebuild, improve or otherwise help their communities.

Blondel was nominated and selected as a recipient of the award — created by developer David Walentas and awarded each year by the Walentas Family Foundation — for her work in housing equity, climate change, Hurricane Sandy recovery, environmental health and Covid preparedness, all of which affect public housing, or NYCHA, residents in Red Hook, a particularly climate-impacted neighborhood. (Brooklyn Magazine is a media partner of the 2023 David Prize Awards)

Blondel, who joins us on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” today, says she will put her $200,000 windfall back into the Public Housing Civic Association, which she started to give voice to and uplift the tenants she represents. Blondel, who grew up in Coney Island and has been in Red Hook since 1982, started her career in cooking and catering, trained as a computer aided designer, construction inspector, a civil engineer inspector and has been a Harvard Loeb fellow.

The following is a transcript of our conversation, which airs as an episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast,” edited for clarity and, to a lesser extent, concision. Listen in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

It’s fitting that we’re speaking this week specifically on the heels of a massive storm over the weekend. How did that affect you in Red Hook, which is famously vulnerable to weather systems like this? How are you guys doing out there?

Red Hook fared fairly well. It wasn’t surge. When we had the Sandy hurricane event, that was surge brought in from the ocean. Almost like a slow-moving tsunami. This was rainfall, and so the basements got flooded, but we were prepared in a lot of the areas with sump pumps, and the ability to keep the water from actually getting to the residential areas. There was some flooding in the greater part of Red Hook, which is outside of the houses. Van Brunt Street. There was some ponding on Mill Street, but, relatively, I didn’t get a lot of calls about people in distress.

Oh, that’s great. I was fearing worse. So it’s not your first rodeo. Hurricane Sandy, which you mentioned, was 11 years ago. For many people, ancient history. They don’t think about it in their day-to-day. For Red Hook, it still remains a daily reality. For you, for your residents. How are you personally still living with Sandy? How is it present in your life in 2023?

All construction is destructive. I always tell people when I was working on mitigation for MTA and for bridges and tunnels, I never knew that along with those remediations came so much noise and other environmental issues. But living inside of the Red Hook Houses, which has been under heavy Sandy resiliency work since at least 2016, it’s pretty grueling.

And it’s not what you would expect. You hear, OK, you get this windfall of money, what was it: $560 million to the community? That sounds good. Reconstruction sounds good. You’re rebuilding maybe hopefully making some improvements. But you’re saying that’s not the case necessarily?

I mean, we are making improvements, but at what cost? So the first two things that really alarm me is the fact that when Hurricane Sandy happened, we naturally lost a lot of tree canopy just because the ocean water is salty, it’s salinated. And that got to the roots of the trees, the mature trees, and we had to take a lot of trees down. Subsequently, in having to put down this new steam lines and electric lines and different things like that, there were 457 trees removed from the Red Hook Houses.

And that was almost like being victimized a second time by the hurricane, because I never thought we would lose so many trees. And then in light of this summer being so warm across the United States, it really concerns me about urban heat island effect in Red Hook right now.

That’s interesting and an unforeseen consequence. You’re talking about the heat, you’re talking about climate change. The city flooded last December, last April, last July. It is simply put not built for the climate change that we’re living in, and it will continue to intensify. Red Hook, as we mentioned, is particularly vulnerable. It feels like an almost insurmountable challenge. Where do you begin to chip away at the threats posed to your community?

Well, there’s a lot of things to chip at, and it’s not just about the topography or the geography of a community. It’s the culture too. For me, it goes back to the great Black migration. Many of the people from my community migrated to New York because they were faced with so many challenges in the south of North America in regards to Jim Crow laws and violence and also housing discrimination.

They simply got tired of it and they felt that New York was more liberal, and they made their way to New York. This is one of the great migration trails of yesteryear. And so we got to New York. We started off in tenement houses or bungalows, which I was born in, a bungalow in Coney Island. We started off in bungalows and then urban renewal came through. And my aunt being an activist in Coney Island at the time actually negotiated with Fred Trump to make sure that residents who were young single mothers living in Coney Island were not excluded from the Model City project. Which brought the housing developments to Coney Island back in the ’70s.

So my family moved into those projects. They were the first tenants, and Sandy in a lot of ways moved them out of Coney Island because they were living on the ground floors. They were completely saturated. My issue with climate change and with the thought of managed retreat is that where do people like me go? I will always remember what happened in Hurricane Katrina when residents were trying to escape the area, and they were met with resistance in other counties. So when I think about leaving Red Hook or leaving New York, I’d rather dig my feet into the soil and stay where I’m at.

And you are a lifelong New Yorker. You are a longtime climate activist and the tenant association president at Red Hook West Houses. But there is so much that you do. If you were to meet someone at a party and you’re introducing yourself, “Hi, my name is Karen.” What do you say you do?

I’m almost like an undercover boss. I really don’t tell people what I do. I kind of try to hope and pray that my work speaks for me. I’m definitely not a perfect person. I’m learning as I’m also teaching what I know. So basically, I’m storytelling — finally comfortable with telling the story of public housing and what we’ve had to deal with in public housing across New York City.

That’s pretty much all I’m trying to do is orientate public housing residents so that they can make better decisions about their future. And that includes possibly RAD/PACT, which is the public/private partnership that will renovate public housing units. At least 62,000 are slated to go under RAD Rental Assistance Demonstration, which New York uses permanently affordable commitment together with developers to bring to fruition. Also, I’m on the Preservation Trust board.

Right. I was going to ask, is this part of the trust to preserve public housing? The new initiative for NYCHA?

No, the trust is separate. So RAD/PACT when that first started, I hated it. It was a federal program that New York City applied to implement. New York City has 176,000 public housing units. 60,000 was going to go under RAD/PACT. Right now, there’s about 15 to 20,000 that have already been converted. Because that was only one idea and there was no other ideas, when the trust was brought up, I hated the trust too.

Can you say why?

But instead of just saying you hate something and not looking at it, and expecting it to go away, I’m trying to train public housing residents that we have to take a deeper dive. And take a look at it and tell people what it is that is stopping us from liking the idea. So I try to build consensus and educate the residents. So 62,000 will go under RAD/PACT. There’s another 25,000 slated for the trusts. Out of that 176,000 units. That still leaves half of the portfolio in need, desperate need of upgrades and repair. So everything’s on the table.

You said you hated it. Can you break down what the opposition might be.

I hated RAD because just looking at public housing campuses across New York City, they vary in sizes. Some campuses are only 200 units or less. Some campuses have 3000 units or more. And so when RAD first rolled out, the federal government made the mandate or the program, but it leaves wiggle room for the state and the city to implement. I didn’t like the implementation. I did not feel like they were engaging the residents.

I felt like they were only engaging the resident leaders, resident council presidents like myself. As a president, I only get one vote. Yes, I get to influence people, but I should be influencing them without bias, and that’s not always the case in public housing because it’s so mixed up with politics and with other people’s agenda.

So my thought was to create the Public Housing Civic Association so that we as public housing residents would have a place to ourselves to meet and to be honest. To be honest about that we don’t understand how to read physical needs assessment. We don’t know when to actually send in a comment on a new policy. How do we start organizing this task into digestible pieces, but in a way where our voices are the most prominent voices, not the politicians, not the nonprofits, but the actual tenants.

Has it been tough to get residents engaged? There’s a lot of ingrained mistrust of NYCHA, I’m sure. How has getting people involved been for you?

So yes, it is tough to get people involved. First of all, people have to see a difference and feel a difference. Trust is earned. It’s not given. And so, number one, the way that we organize in Red Hook, we organize across all of our nonprofits and stakeholders. By doing that, we start to build a bond across the community which creates social cohesion.

So if you come into Red Hook and you want to know about the coastal resiliency process that’s happening in Red Hook, most people will point you to me, and then I may point you to Resilient Red Hook or to RETI, Resiliency Education Training and Innovation. Because those are the community partners that most deal with that particular topic. If I’m going to deal with policing, I may deflect to our Red Hook Community Justice Center and the Red Hook Initiative.

One is part of the penal system, but it is a community court which has a little more wiggle room than traditional courts. The other one uses restorative justice. And so, as community members, we have to stay on top of this to make sure that our agencies, whether it’s punitive, or not being too punitive without understanding the extenuating circumstances. And also, for the groups that are using restorative justice, not to be too lenient on our residents as well. We use this model in place of the fact that a lot of public housing is not equipped with two parents, so we kind of parent our community in that way.

Tell me a bit about Red Hook Houses, the largest NYCHA development in the city, right? You’re over at Red Hook West. You moved there in 1982. There’s some 1400 apartments, 3000-plus residents. What do you want people to know? What do you want people to know about Red Hook Houses, Red Hook West? What’s the headline?

So the headline is, Red Hook West is ready to level up! I do believe based on your network and your connections, you can aspire to be more affluent than influential. And I think that in Red Hook we have created somewhat of a model of how we want communities to engage with each other. We did the same model in Gowanus by creating a Gowanus Neighborhood Coalition for Justice. And it’s working pretty well.

We have an oversight task force with a facilitator, James Lima and Ben Margolis. Just looking at that work that we did, I’m looking at how it has expanded, how other people are now getting involved. But also, the challenges that are still there in regards to some of our points of agreement. And so, looking at that model and going back over there and saying to that coalition, if we are saying this and we are the industrial business zone, and we’re the small business developers, and we’re the nonprofits, what do you think is happening to the public housing in that area which may have less of a connection or resource? I look at those as little flags to make sure that things are going the way they’re supposed to go, and if not, then we just have to raise the issue.

How are things going?

It’s going pretty well. Red Hook is known for putting in a 197A plan back in the ’90s. That was a neighborhood saying to its government, “These are the things that we want in our community.” I believe we got at least 30 percent of what we asked for back in the ’90s. But we should take a look again at that particular data. See what we need to adjust now that we’ve been hit with climate change, and fires coming from Canada and pandemics. What else do we need to do to make sure that we not only survive in Red Hook but thrive and become a model for other communities?

One of the reasons we’re talking today is because you’re one of the recipients of this year’s David Prize. Congratulations. What does that recognition, and more importantly, what does that infusion of cash mean for you? What do you do with a windfall of $200,000?

First of all, I was nominated. I didn’t apply, and so that felt amazing to know that other people are recognizing my work. As far as the David Prize, I’m very grateful for it. But I’m also cautious, because again, we have caste system in New York, the money is not tax-free, so I do have to pay taxes on it.

Is that right? I did not realize that, OK.

But I’m also holding my breath to make sure that New York City Housing Authority or nobody else tries to take it from me before I can put it to good use.

What’s the number one priority with it? On day one, taxes are paid off. You’ve gotten it away from NYCHA, what are you going to do with the first dollar?

I want to start a cohort. Being a president of Red Hook West, it’s an amazing position. But you don’t always get to pick who you work with, and you have to be open to everybody. With the Public Housing Civic Association, I want to be more concentrated.

I want to concentrate across the five boroughs. I’ve met so many amazing organizers, including some that are opposition to the trust who are in opposition to RAD/PACT. But I would still want to invite them as a part of the cohort to learn so that we all know exactly what these choices are, and we can all be on one page as to getting rid of the myths around it.

Because I hear a lot of people talk about RAD/PACT, public/private, and they lump the trust in as if the trust is privatizing public housing. And it’s not. The trust is another NYCHA with a different name. And as a person who’s also spiritual, I believe you have to change your name if you’re going to change your game.

And so I like the fact that NYCHA is going to have a new name other than NYCHA, New York City Housing Authority. It will be called the New York Preservation Trust. So that gives us a chance to change the character or change into best practices from things that we don’t like that were going on under New York City Housing Authority.

When does that change go into effect?

It’s already in effect. These changes went into effect after the southern district came out with its demands to the Mayor. At the time, it was Mayor De Blasio. And it demanded that NYCHA do a transformational plan. They have done a transformational plan. It’s being implemented. One of the things I work on is work order reform. So a work order reform is a neighborhood model that instead of a carpenter or maintenance worker who can do simple repairs like fix a faucet or socket, that person now, if that person comes into my house because I need a repair. And he comes in and he’s unable to complete the repair because I need skilled trades, he has to give me a ticket. And on that ticket is a planner’s phone number. He has to competently mark who I need. Do I need a plasterer? Do I need a plumber? Do I need an electrician?

He has to mark those things off. So that’s a way for us to look at how competent the maintenance worker is, number one. Number two, the tenant now makes the phone call to set up the appointment. That’s better than somebody just knocking on your door randomly when you’re not home.

So now the tenant sets up the appointment for the electrician or the carpenter or any of the skilled trades to come. If that person doesn’t show up, the planner knows every single one of the skilled trade schedules. So we will be able to stamp out people who are not doing their job competently, people who are saying that the resident wasn’t home, people who are not coming with proper equipment. All of these things are being found out through this new model, and it has definitely improved NYCHA, but there’s still some ways to go.

As the president of the Red Hook West Houses, you’re elected into that position. And forgive me for not knowing off the top of my head, is there a term length, a term limit? Because you are there at the will of the people. And obviously, as long as you’re doing a good job, you’ll be in that job. What is the path forward for you?

That’s one of the reasons why I became the president of Red Hook West. I’ve been an active member of the Red Hook West Tenant Association since the ’90s. And it took me forever to get a copy of the bylaws. And now looking at the bylaws, they’re from the 1990s in Red Hook. In other developments, the bylaws go back to the ’60s.

Wow.

That’s a red flag for me. As a person who just finished telling you about The Great Migration, civil rights, that doesn’t sit well in me that we are not looking at the one thing that actually governs an organization, which is its bylaws. So one of the things that we’re doing, or one of the things I want to implement and I’m going to ask the residents is I want no president to be a president more than two consecutive terms.

After that time, you should have to step down for one term. And then, if the residents want you back, you can always apply the next term. But there should be a break in between because people in public housing are vulnerable, a vulnerable population. And too many times I see us caught almost like in a field pen, because nobody put in the safeguards like that, that we need. So I personally would not do more than two terms before stepping down, and the terms last for three years. So we are two years in, and we have another year to go before we have to do an election.

Got it. OK, and as the sort of full-time advocate for tenants, you’ve given some sense of what you’re dealing with on a day-to-day basis. You’re dealing with incomplete lead paint inspections, repair delays despite oversight. How do you prioritize what you tackle? What do you put on the top of the list?

Well, number one, I come with an engineering background, so that helps a lot. The fact that I can read a blueprint. We have to be comfortable as public housing residents with learning new skills, and also with having some type of mechanism where we can go to each other and say, “Karen or Barbara, I don’t understand this. Can you help me?” I still don’t see that happening, though we have many public housing campuses across the city. It’s very fragmented.

It’s interesting that you mentioned your engineering background. I’d love to talk about your background a bit because your background in itself is so diverse. You started in cooking and catering. You trained as a computer aided designer, construction inspector, civil engineer inspector. You’re a Harvard Loeb fellow. What is the through line in all of that work?

I think that when I was 17, I wanted to go into something like engineering, but my mom died of complications through multiple sclerosis when I was 15. I saw a brochure for Job Corps. I thought it was college. So I said, I’m going. And at 17, I jumped on a plane and went to Utah, which was probably the first job corps center. I got there. We served over 3000 young people, including myself, and the first thing I saw was this bucket with this liquid yellow stuff. And I said, “What’s that?” They said, “Well, that’s your breakfast. That’s eggs.”

I said, “Well, that’s not my breakfast,” because I wanted to see a real egg, in a real shell that you crack. So I quickly changed from being in engineering and the trades into wanting to be a chef. And I think that that was a positive move. I believe that what we eat, really the fuel that you put in your body is what maximizes your brain, and everything about your being. And so learning about food very early was a plus for me. I also worked in commercial cooking and catering. Because after rent, groceries is the next highest bill you have to pay.

That’s right.

So I was trying to cut corners when I was young and still eat really good. So I always worked in executive dining and stuff like that. It was a great experience to be around food and to enjoy, be passionate about preparing things for people. So I’m a servant. You have to be a servant mentally. And if you’re a servant, that means that [is what you] do from serving a plate of food to serving policy to your community.

You did have a little bit of the engineering background that you picked up later along the way. What galvanized you into the climate aspect of the work? Was it Sandy? Or did you already have an eye on that?

No, it was this lady named Sabine Aronowsky at Fifth Avenue Committee. She’s my friend. She’s my Lucy and I’m her Ethel or vice versa. And so I heard that Red Hook was getting a half a billion dollars, and I knew that was big. I knew that, that wouldn’t be seen again in my lifetime, I didn’t think.

That was after Sandy.

Right after Sandy, when I heard around 2015, “Red Hook is getting $550 million.” I was like, “What?” So literally I was ready to quit my little engineer assistant job. Because I was so curious to know what $550 million would mean for a campus like Red Hook. Fortunately, I ran out and I started making my own flyers.

This is before I was president of anything. I was like, “Residents get to this center. I want to talk to you guys.” And this lady, Sabine Aronowsky, came and she had an application where she was looking for a organizer for a project called Turning the Tide Environmental Justice Group. It was a Kresge grant.

And so I wanted to know if I could organize for Red Hook, so I wanted to wet my feet. So I took her up on this offer. I took a pay cut of about five to $8,000. I can’t remember right now, but I took a pay cut, and I started with environmental justice organizing.

And I said, “What is environmental justice? They’re giving me the hardest thing to start with!” I couldn’t just be a regular organizer. They had to give me this hard stuff. And so we started with, “What is an environmental injustice?” And we delved into that, and we started talking about the Gowanus Canal cleanup. And every time we tried to talk about the Gowanus Canal cleanup, the residents kept saying, “No, I want to talk about my indoor environment.”

I started telling the powers that be as important as the Gowanus Canal cleanup is, this population can’t see that because they’re dealing with no heat, no hot water, mold, lead crisis mode constantly. I said, “As a matter of fact, outside of this Gowanus Canal cleanup, they’re proposing a rezoning, and the residents are not even included in the rezoning.”

So we took our environmental justice organizing, which came with an eight-month curriculum that we created, and we went the next step with that and created this Gowanus Neighborhood Coalition for Justice. Where we were able to authentically get the entire community to say the number one demand is you have to fix local public housing.

It’s a lot of work. You have a lot on your plate. Talk a bit about growing up, because you mentioned this. You grew up in Coney Island. For many people it’s this weird throwback fantasy land. It’s charming, gritty, it’s fun. What was growing up there like?

Well, being a kid in Coney Island is fun. You see the rides. Every time you go to the Boardwalk, the rides were right there. I remember hot dogs were like 10 cents. I also remember there was a movie theater straight across the street from Nathan’s where I watched … “Jack and The Beanstalk” was the movie back then. And at the time I was with my stepmother. I used to terrorize her because I never wanted to leave the movie theater, so I would throw a tantrum to make her stay and let me watch it again and again.

You were a little boss too.

Very much so. I learned a lot being the president of Red Hook West, that I am more controlling than I thought I was. But I’m also learning to let go. I’m growing, and I think that, that the sign of a good leader is that it’s not about leadership per se, but it is about growing with your team and having your team grow as well.

That self-awareness is important and probably hard won. What’s a typical day in Red Hook like for you when you’re not working for your community, not working for your tenants, not working against climate change? What do you do to relax? Where do you hang out in Red Hook? What’s a nice day for you?

So Red Hook is full with artists, creatives. We have Pioneer Works, Dustin Yellin, who has an amazing story. We have Florence Neal at Kentler Gallery. She does Saturday classes with children. She’s constantly giving some kind of residency to artists so we can learn different things like wood carving, or the color of your water. About other areas because they move around. They go to Brazil, and they come back with artists and with information.

We also have the Red Hook Arts Project. That was something that if that girl, Tiffiney Davis, was older than me than vice versa, I’m older than her, I probably would’ve used her effectively for my son, who is a natural artist. But at the time he went to LaGuardia, he was also experiencing some cardiomyopathy as a teenager. And so he had a difficult time really embracing his talent. He didn’t have a portfolio. There weren’t a lot of places to really help young kids put together portfolios and express their self. Well, Tiffiney Davis came up with the Red Hook Arts Project, because her son was having the same issue, and she’s also amazing.

The scope of your work is so broad that it’s hard to get too specific about any single aspect of it. What do you want to leave listeners with?

I want viewers or listeners to know that I am a liberator. I look at the world almost like a person who’s leading an orchestra. Even though I deal with a lot of broad and different topics, I can connect the right people to those topics. And that’s what I want to embrace. That’s what I want Public Housing Civic Association to be about, so that it’s not only about caring, but I’m actually connecting the assets that are in our community into the right spaces that they need to be in so that this can start functioning on its own.

Red Hook, to your point, is so amazing. And there’s almost like two different Red Hooks. There’s, you have the Red Hook Houses and the surrounding areas. You’ve got the pool and the ball fields. But then you also have the artists and you have the gentrifiers who’ve moved in and are pushing prices up.

It’s OK. Number one, we don’t have a lot of transportation. Number two, we have a huge IBZ, industrial business zone, and that’s dedicated land. So that’s another thing. I used to walk around and call myself the Fearful Princess when I was young. I’m now the Fearless Princess.

I don’t let any talk put any fear in me. I go and get the data. I do my research. So again, Red Hook has so much, like you said, parkland. Parkland is dedicated land. If anybody tries to touch parkland in Red Hook, they’re going to have a fight. Because we will protect parkland, and we will also protect the IBZ because that’s what keeps Red Hook the way it is.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like