Photo illustration by Johansen Peralta

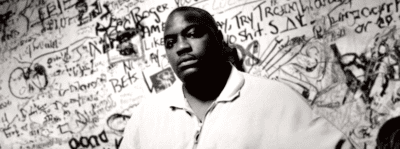

The reformer: Erika Sasson on pushing restorative justice into new territory

'Here's how you replace the criminal justice system that has failed so many people,' says the 2023 David Prize winner

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

The American criminal justice system is built on a punitive ideology. It is an ideology that believes criminals deserve punishment and that punishment can change behavior, that criminals will accept responsibility through punishment, and that the infliction of such punishment will deter criminal behavior. Of course, as we all know, it doesn’t always work out that way in practice.

The Brennan Center for Justice in a series of essays in 2021 concluded that the criminal justice system is marred by an over-reliance on excessive punishment. “At the most fundamental level, we must ask unsettling questions about the impulse to criminalize and punish, especially as this impulse has been applied selectively through American history,” they wrote.

There is another way.

Restorative justice is an alternative to incarceration. It is an approach to justice that aims to repair harm by providing an opportunity for those harmed and those who take responsibility for the harm to communicate about and address their needs following a crime. Erika Sasson is a Brooklyn-based lawyer who is taking this kind of practice into new and challenging territory by using it for homicide and domestic violence cases.

By partnering with district attorney offices across the city and establishing a team of co-facilitators, Sasson, who works on her own, implements a process over multiple years whereby participants, both families of victims and those accused, take accountability. They heal. They move forward.

Sasson joins me on this week’s episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” to describe her trailblazing and empathetic work in restorative justice. It is for this work that she was one of five New Yorkers to be awarded the 2023 David Prize. An annual MacArthur Genius-style grant for New York residents, the David Prize is a no-strings-attached gift of $200,000 to locals doing on the groundwork to rebuild, improve or otherwise help their communities.

Sasson says the infusion of cash is both a welcome bit of recognition for her work and it will buy her some time. We discuss the work itself, which is rooted in the belief that courts and prison are not an effective means to get to desired outcomes at all times. We’ll talk about how restorative justice, which has proven to be extremely effective for low-level offenses, can be applied to seemingly impossible violent crime cases, though it is by no means a cure-all.

The following is a transcript of our conversation, which airs as an episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast,” edited for clarity. Listen in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

Before we turned on the mics, you were in the process of explaining to me the meaning of the name Sasson. What’s the origin of the name? You’re not related to Vidal Sassoon, are you?

No, I’m not. I’ve always wished, but I am not. It’s a word that means joy. It’s actually a very restorative justice kind of question, which maybe you don’t even realize, to ask the origin of your name. It’s like an old peacemaking tradition.

Oh, interesting. I love name origins.

It’s from Iraq. It’s Sasson, it means joy in Hebrew. So, I like to either live up to it or really disappoint people with that as my last name.

Yeah, that’s setting the expectations high. I like to underpromise and overdeliver, but we’ll see. This is joyful so far. You design and facilitate restorative justice processes. May or may not be familiar to our listeners, but you take the practice to a new level using it for homicide and domestic violence cases. Can you just break down what restorative justice is at its root, and then we can get into what you’re doing?

At its core, it’s focused on the people that are at the center of the harm, and it asks them, “What happened? What is it that you need and whose obligation is it to respond to that need and really fix it?” It’s a framework that shifts our focus from punishment. And it certainly doesn’t think that punishment is accountability. Instead, it’s focusing on who are the people really at the heart of a problem, of a conflict, of a harm, what do they need, whose responsibility is it to fix that, and how are we going to move forward in a good way. It’s really rooted and inspired by many indigenous traditions that have been practicing that for a long, long time and continue to practice it today. I would say it’s a more sacred way of thinking about what justice means to us.

And it goes counter to what our legal system is designed at its core to do, which is punitive and it’s baked into the language, like “victim” and “defendant.” You don’t like those words. Can you give an example of this working practically on a day-to-day level? Where do you see restorative justice most commonly deployed today?

Well, that’s a complicated question because where it’s deployed is not necessarily where it should be deployed. But let’s just say that there’s a lot of research that actually says the more violent the crime, the more effective it will be. So, probably where it is mostly deployed, is actually in these offenses like theft or nonviolent offenses or cases only with minors. And that’s where people want to use it. But the research is that the more elevated the emotional injury and the physical injury, the more you’re going to get out of it.

If we think about it in the more day-to-day … You were telling me [before we started recording] that your dog is out being walked. Imagine being outside in New York City and something happens with your dog, and you get into a fight with your neighbor because he’s seen you walk your dog. He thinks that you’re not picking up after your dog, and he is getting really agitated. And who knows what’s going on inside his house. One day something breaks and one of you injures the other.

Just as long as the dog’s OK.

Let’s say you’ve punched someone in the face because let’s say he kicked your dog. How about that?

Oh, no! Buddy.

I’m so sorry for your dog. But he kicks your dog, so you shove him. And then, another neighbor calls the police who watches this whole thing happening. And so, if you imagine this case going into the legal system, you can imagine one of you gets arrested. So, it’s you in this case, nobody saw the dog get kicked but you. You get arrested, and you’re both separated. And the first thing your lawyer’s going to tell you, and your lawyer’s right to do this, but your lawyer is going to say, “Don’t say a word. Do not say a word ever to your neighbor. We’re going to handle this. We’ve got this.” And your neighbor is going to talk to the prosecutor, and they probably won’t tell them that they kicked your dog beforehand. This is all going to be put into the shadows. And the aim of restorative justice in this case is to look at the practical facts. People think it’s really either touchy-feely or it’s easy on people.

Whoa, whoa. Yeah.

But what I’m looking for is the fact that you’re not going to move, like, homes. Your neighbor’s not going to move. Nobody can afford to move in New York City. So, what’s the practical and safe thing is to help you both figure out what happened and how to fix it. And so, I see it as an intervention that’s trying to actually help you tell the truth. “Yes, I did punch you in the face. I’m not going to lie to myself or others about that. It was wrong. Also, you kicked my dog. That was wrong. Can we hold both in this circumstance?”

It’s about accountability, and it’s about addressing the root causes for your actions and owning them. And it’s funny because I was Googling around on you, and you wrote a piece after the Will Smith apology for slapping Chris Rock, a very thoughtful piece dissecting that apology and why apologies matter and how you apologize matters. And that all plays into this, what makes it a meaningful apology, which is different from restorative justice, but I guess a component of it.

It is different, and I certainly tell people I’m not in the forgiveness business. Forgiveness is so personal. It’s up to you and your neighbor how you’re going to move through this. I would never impose that agenda on people. I also would say that what I would say now about apologies doesn’t necessarily apply to Will Smith and Chris Rock. That’s also between them. So, one of the most important things about an apology is that it’d be between the people who are most impacted. So, I thought that the Will Smith video had a lot of merit to it. It obviously wasn’t to the person that was harmed most directly, but I would think an apology takes time.

There’s many ancestral traditions that tell us how to apologize. In the Jewish tradition, we have Maimonides who really wrote the book on this, how to make amends. What I thought was meaningful and what Will Smith did was that it was without taking on the shame. One of the drivers of violence in our society is this idea of shame, of being so humiliated that you have to show yourself and show your hand. And then, we cover ourselves in shame. So, we shame people who are called defendants in our system. We tell them, “You’re the worst. You’re the ultimate worst.” Then, they feel more shame and then they commit more violence. We see that as a driver in the cycles of violence. So, I think one of the most important things is to push away the shame and really get at telling the truth about what you did and doing that in relationship with somebody else, and asking what they need: “What is it that you need? I acknowledge that I did this. What is it that you need?” That would be a basic way to start.

And in the case of the guy who kicked my dog that I punched and went to jail for, I own that I punched him. He will hopefully come to admit or own or agree that he did harm to my dog, and then we have to live next door to each other. How do we move forward without this festering over time? What is the next step there?

A key piece of it is it’s not just about you and your neighbor, right? It’s also about the person across the street. It’s also about the people that you live with in your home who are all carrying the impact of what happened between the two of you. So, it’s about all of you impacted coming together about agreements and saying, “I agree to…” let’s say your neighbor says, “Please just get your dog off my lawn.” “I’m sorry, I should never have done that. I was going through a personal thing. I totally overreacted. My bad. Would it be possible for you to not walk your dog on my lawn?” If you’re lucky enough to have a lawn in New York City.

Yeah, who’s got a lawn? My neighbors don’t have a lawn.

“And for you, I’m tired of you playing your music really loud.” Whatever it is, and just saying the thing that’s actually bugging you about the other person and trying to find a way to move forward.

But your ultimate vision, and one of the reasons why we’re talking and probably why you won the 2023 David Prize — congratulations — is to transform New York into a city that prioritizes alternatives to punishment, offering opportunities to growth, healing, safety, but in the realm of violent crimes. You’ve done this successfully with violent crimes. I know that you’ve written about one murder — or there was a death, and someone was responsible for the death — and then you got those parties together. Walk us through what you’re doing that’s taking it to the next level.

What I’m trying to do is show that this isn’t just for Brian and his neighbor, that we can think beyond that, that this is something deeper about how we relate to each other. And that even in really difficult circumstances and in areas in which both the advocacy community, the justice system community, reformers, all kinds of people, we just don’t touch that. And there’s always this area that you can’t encroach on. And I’m really curious, ultimately curious, what does it mean that we’re interconnected? What does it mean to soften the lines between us? Where do those ideas go into? And so, I’m curious, what about domestic violence? It’s a huge problem that has not been solved at all by our legal system. What could be there instead of what we currently have so that we can give more people options? It’s really like for me, a path of exploration, of critical thinking, of curiosity to say, “Let’s go deeper. Let’s go to places where in New York City we really haven’t spent a lot of time in, and let’s see what are the beautiful things that we can create in moments of difficulty.”

How much resistance do you get, or how challenging is this? We were saying the way the whole system is built is to be punitive. I would imagine even getting the parties involved in the case, whatever it is, is challenging. It’s politically challenging to apply this to violent cases. How receptive is legal community to this?

I think there’s some funny challenges. Sometimes people say, “OK, I’m ready for restorative justice. What’s your evidence? Show me that it works.” And I’m like, “Well, you just invited us to the table 20 minutes ago. So, I have evidence that your system isn’t working, but you want the evidence that my newly admitted practice is evidence-based. Where’s the randomized control trial of this?” All that kind of way of thinking. So, I think one of the challenges is saying, “Hey, we’re getting going here, and we need time to catch up with our systems who’ve had a long time to do what they’re doing. Sometimes well and most often very not well. Those of us who are trying to try new things, we need support. We need to know that this is a valid aim and that we should keep trying it.” That’s one major challenge is how impatient people are for results when we’re moving in new territory.

In a case where you’re applying restorative justice, it takes longer than if it’s just run through the normal legal channels? Or it can.

It can, but really the legal channels take a very, very long time, and they’re not really rushed. So, we have people who are detained in Rikers Island for a long time without trial. Nobody’s like, “Hey, what’s going on over there?” If there’s a homicide, the clock stops. So, there is a right to speedy trial here in New York, but you won’t have that right in the case of a speedy trial. So, it can take three, four years to resolve a homicide case here. There’s these different standards, and I feel like the standards for those of us who are new and trying to do something new are a little bit different than the low bar that I feel our justice system has to clear.

So, talk about one of the cases that you did. I mean, you wrote very clearly [about] a homicide — I don’t even know if the language is correct. There was a death and someone was at fault, and there was a survivor. Can you talk about that case study of restorative justice where there was a death?

Yeah, and I’ll just say one more thing to your question I think is important. This is really counter-cultural. That’s just the bottom line is that to say to people, “We can come together. It doesn’t have to be like this. There is another way, there is a third way, there is a fourth way, and we should try them all in the face of harm. We should be trying whatever we can to give people grace, to give people something beautiful, quite frankly.”

This is exactly to your point; it’s not the way legal training is set up. It’s not the way law schools are set up. Most lawyers are not prepared for this kind of work or mind frame.

In our daily lives, we’re not prepared for this. We want clarity. We want to say, “You’re good and you’re bad. You’re wrong.” I see the value in it. Sometimes I miss the legal landscape; I miss the clarity. I miss being on one side, but I’m not built for it. But to just walk you through that case, then, I’m going to talk more generally to protect people’s privacy. But if you can imagine pulling a gun on the streets of New York and killing a bystander, being in some altercation, using your gun, killing somebody else, what do we do in that case? I mean, it’s a horrific, horrific crime. People are left devastated. And it’s not just the family members who are devastated. First of all, the family members on both sides are devastated. So, if your son is arrested — if, God forbid, your family member is killed — that’s just incredibly difficult for them. But then, everybody in the neighborhood too, who’s feeling unsafe, who feels like they can’t walk down the street without feeling the stress, there’s a wide ripple effect. What would I do in a case like that?

First of all, let’s look at what our current response is, and I understand why the response is this way. I just think we could do better. So, the current response is find the person who did this, prove that they did this, and send them to prison. For some people, maybe that works, but it doesn’t help people move forward. In these kinds of criminal trials, nobody is saying what they did. Nobody is owning it. You just get this muted system; this thing happened, and you get that from the courts. The courts eventually say, “This thing happened, and it’s worth 20 years in prison.”

That’s all you’re getting from the court. And what I’m trying to do is get a little bit deeper with people and hear from the person who caused this really unspeakable harm, have a conversation. In most cases, it’s many, many conversations. So, to your point of how long it takes, maybe about a year of getting to know someone who has caused this harm, spend time with them, hear about their family, hear what’s happened to them first.

Most people, you have to hear what happened to them first before they’re able to acknowledge what they did to somebody else. And so, you go through a long process of really slowly chipping away to understand what was going on for that person, what are the conditions in their life that led them to that moment, what are the conditions if they’re incarcerated that are continuing to be incredibly difficult for them. And then, let’s talk about what happened.

And so, most people, your lawyer, if you’re a defense lawyer, the prosecutor, no one says to you, “OK, are you ready to talk about what happened, what you did? What does it feel like to own that?” That’s a very hard conversation. And we skip those conversations for the most part in most areas of our lives. And so, it’s really about foregrounding that difficult conversation with love, with support, without attack, so that you can get to something precious.

And you would need to have the defendant’s lawyers on board for this process? It’s not just a one-sided thing. That’s a whole another set of convincing you need to do. It’s not just the person involved in the altercation, but the person representing them as well.

Yes. And on the other side, it’s also spending time with the victim’s families who are heartbroken and some of them are curious. Like, “Who is this person who did this to my loved one? And I want to look them in the face. I actually want to hear about them.” When we think about our relationships, we think, “OK, it’s like you and your neighbor. It’s you and your family.” Those are the relationships in our lives, me and my neighbors.

When a harm happens, there is a relationship that is created between two people, even if they were strangers beforehand, they’re both connected by this event. And for some people being separated and never seeing that person again is the right thing. But for other people, acknowledging that this event has changed my life and that you, this you would this other person, you are at the heart of that, and I need to talk to you. I ultimately need to talk to you. I can’t just push it down and never look at it or pretend you’re not here or send you to prison and never think of you again. It’s not going to work for me. I’m going to carry it. It’s going to sit on my chest, and I won’t be the same. So, what I’ve seen in these kinds of cases is … I spend a lot of time with both sides, just a lot of time, and same level of empathy and sharing and connecting on both sides. And when people are ready, it means they know what happened, and they know how to focus on the other person, and they know how to listen, and they’ve been listened to enough to be able to participate in this.

Got to be exhausting for you.

It’s so beautiful. It’s such an amazing thing to be part of. It’s tiring certainly, but it’s also, I feel so lucky to be able to see people do these magical transformative things. I told someone recently, “I’m just like building the car, but you’re going to drive it.” To watch them drive it after you’ve been assaulted or sexually harmed, to watch someone get into their car and drive it and be like, “I can do this.” Don’t feel bad for me. I feel great.

Well, I don’t feel bad for you, but you get them to the point where you’re going to get in the same room together, and then that’s got to be a whole other moment.

Well, that’s where I’m really vigilant. That’s where I’m using every single trick of the trade, everything to make people be able to hold and stay and get what they need. I never want you to be forced in there. I never want it to be worse for you. The worst thing we could do is make it worse. So, it’s really about what do these people need and being really careful in helping them get what it is that they need.

Are you seeing trends or themes in what people need or is every case different?

These cases are self-selected in the sense that I’m looking for people who want this. I’m certainly not looking for people who don’t.

How often do you get turned away? Obviously this is not a key that fits every lock. How far down any path for any given case do you go before you realize this is just not going to work? How often does that happen?

Well, sometimes you don’t want to bring people together because they’ve gotten what they need from these separate conversations. So, there’s that, and that’s happened a number of times. I worked with a survivor who said, “I actually think everything we’ve done in these private sessions and me knowing that you’re working with the person who abused, that’s enough actually for me.”

“I don’t need the face-to-face.”

I don’t need the face-to-face. And so, in that moment I say, “I’m so happy that you figured out what you need and that you got what you need, and let’s call it.” It’s things like that. So, sometimes you take people to that moment and when people say that’s enough. Normally, in the first conversation, I’m able to see where this is heading. And I’ve told people in the first conversations, “Did somebody recommend that you should do this? Because I don’t think you really want to do this.” So, that’s what I don’t want. I don’t want people to do that. To your question of how many people would want this and how many people wouldn’t, I think a lot of people don’t know it’s possible. Don’t know to ask for it. I think we’re skipping a lot of opportunities. If you can imagine back to you and your neighbor, imagine you guys could just both … Two situations, one in which this case goes on for two years and you’re uncomfortable in your home for two years or over the course of six months, you figure out a way to make it livable. You’re not best friends, but just livable.

Do you do this under the auspices of a law firm? Are you a private practice? Where are you coming from? I know that you are the founder of the Red Hook Peacemaking Program, which is separate. We can talk about that. Is this private practice? How do people find you?

So, I worked for a long time at an amazing organization called the Center for Justice Innovation. That’s where the Red Hook Peacemaking Program was launched. It was a really big-umbrella organization that’s trying out all kinds of things around the city. So, most of my experience came from there. And then, a couple of years ago, I went out on my own to do really difficult cases and really risky cases that don’t have a blueprint. It feels really good to do that on my own and to take as much time as I need for a case. What I’m trying to do is take these landmark cases and show what it takes to go all the way with people in areas that other people aren’t willing or don’t have the time to do. So, right now, I work on my own. I do get some private funding that helps me to offer this for free to people.

I was going to ask if these are pro bono.

But I don’t get paid by legal parties, and that’s really important because I don’t want them to think that they’re my client and they’re like, “Hey, give me my reconciliation already.”

So, the David Prize comes along. You’ve got $200,000, no strings attached, although taxable, I guess. Where do you spend your first dollar? What is that prize going toward, or have you figured that out yet?

I haven’t totally figured it out. I would say it’s amazing. So, the fact that they’re giving you this money is amazing. If you’re like me and you’re working in this nutty area, and you’re out in the corner just thinking, “I think it would be beautiful if we could do something differently.” And then, this organization comes and elevates you in this way and says, “Yeah, I think your ideas are beautiful.” The affirmation and the support has been maybe a big piece of this. People are thinking about applying, and I think that it’s still open, the deadline.

For next year.

Yeah, I think about it that way too. I’m working contract to contract. I’m on my own, and the idea that I can stop for a second and say yes to a bunch of speaking engagements, so in the next six weeks, for example, maybe this is the right way to answer this. In this moment, in the next six weeks, I have about six different speaking engagements. And most of them are not paid. So, it helps me to be like, “Yep, I will give you in this arena, in that arena, in that arena, whatever knowledge I have to be able to share it and not have to be able to feel that rest and the sharing of information.” That’s the first thing for me is, how do I share more of this information? The article that you referenced, I wrote that. They had already told us that we won.

That was in Vox, I believe.

Yeah, in Vox. Being able to write that article, that’s for me already something that came out of the David Prize. So, for me, it’s a lot about training people, sharing information, giving access, maybe doing some cases, pro bono, all of that. Rest is part of it.

Rest is important. I wonder if you could go back because you referenced this earlier, maybe this is ping-ponging a little bit, but the idea that the right to remain silent can be hurtful. I wonder if you can unpack that a little bit.

So, I think first of all, if you’re listening and you’re arrested, you should remain silent. It’s a really important right, given the structure, given that your liberty’s at stake, and given that fact that when your liberty is taken away, you’re put in places where the conditions are inhumane, degrading, problematic for a host of reasons. So, I don’t want people to lose their liberty. The path to that is to remain silent, but that’s thinking about the individual in that way and with that very important need being met, which is to not go to jail.

But when you think about coming to terms with who you are, what you want to be, what you did, when you think about what does it take to do that work, and everybody has that capacity inside of them and those questions inside of them about who they are, there isn’t a person on our planet who isn’t asked, “OK, well, I know I did this, but what did it mean to me and who do I want to be?” All those really important questions that bring about, first of all, personal healing for somebody who’s caused harm, but then also help our community because when they go through that, they are less likely to commit more violent offenses. When we get people connected to the supporters in their community, when we help them have these important conversations, our whole society improves. That’s I guess our theory of change is that telling the truth, and you can think about it, everybody listening can think about when you’ve told the truth what that’s done for you. When you’ve gotten that weight off your chest.

“The truth shall set you free.”

They say that. It sets a part of you free, and living with the weight of a secret can really impede your relationships.

It made me think of another, maybe pat saying that…

More cliches, we need more cliches.

Yes, more cliches: Hurt people hurt people, which is what you were alluding to. I don’t know if you roll your eyes when you hear people say that, “hurt people hurt people.”

I think it’s true, and I think also a lot of hurt people don’t hurt people. And so, we have to help people who are hurt, and we have to help people who are hurting people. It’s just like, what is our intervention worth if we’re not acknowledging some of those things?

So, outside the legal system, we mentioned the Red Hook Peacemaking Program. It’s a traditional Native American approach to justice, to focus on healing rather than punishment, much like restorative justice; you helped set that up. That’s down in Red Hook here in Brooklyn. What is it? What does it do? What do you want people to know about it?

It’s been going on for over 10 years now.

Has it been that long? Wow.

Yeah. I think I was pregnant with my 10-year-old. There we go. It is a program that is really centered on Navajo peacemakers’ wisdom. They’ve come to Red Hook year after year for most of that period to train local residents in this approach of peacemaking, which is very connected to restorative justice. These are connected traditions. The Navajo peacemaking tradition was something that we at the Center for Justice Innovation were studying, we were learning from, and we wanted to see what it would mean to bring that into Red Hook at the time.

I know you interviewed Karen [Blondel]. There’s amazing elders in Red Hook, amazing people and cultures of people who look out for each other and are natural peacemakers. They really took to the idea of these Navajo elders coming into Red Hook and sharing their way. Many of them at the time would say, “That’s how it used to be around here.” It just really resonated. So, we took these different approaches and brought them together. And the idea of the program is that these residents are trained in such a way that they can take conflict, either that come from the Red Hook houses or come from the community or come from the court that’s there, the community court that is there, and they’re able to resolve it much in the way that I described by listening to people involved and sitting with them in such a way as to help them think about what it means to move forward. So, that program is ongoing and is really focused on Red Hook residents helping other Red Hook residents.

You studied indigenous communities. You went to Ecuador during your studies, did you not? You’ve sat with indigenous tribes and learned how they think about justice and punishment … or not punishment and accountability. I wonder if you could talk about that experience a little.

That was in my first year of law school. I went to law school at McGill.

I love Montreal. It’s great.

That’s where I grew up, and I went to law school at McGill. And in my first year after law school, I went to Ecuador, and I worked with a human rights organization that was trying to help indigenous populations around the country affirm their constitutional rights against mining companies that were coming to take their resources. So, we were doing trainings there. And while we were doing the trainings, they asked me to do a separate project on a specific indigenous tribe called the Awá, and looking at their approach to the administration of justice. And so, we traveled to these communities that you could only get to by foot deep in the cloud forest.

I haven’t talked about this really ever. These really incredible places, very, very remote. What was really important for me in that experience was that their first language is Awa Pit. And so, Spanish was their second language. So, I’m speaking in my bad Spanish and their second language Spanish, and we’re meeting in this middle here. I’m trying to hear about, “OK, what does it mean that you use corporal punishment?” Because they use whip. At the time, they used a lot of corporal punishment. They used something called the rack out there, and it was very shocking to me.

That doesn’t sound restorative.

Over time, spending time with them, I was able to understand that they do those things, but they also talk to the people who cause harm. They tell the truth about the harm, and they’re trying to keep you here. If you want to stay here, we need to really talk about what you did. So, there was corporal punishment, but there was this other element that I thought we were missing. And just by spending time hearing them describe the way everyone in the community would tell you what you did was wrong, felt like a huge departure from our very silencing process that we have here. It impacted me, certainly.

I don’t know if you see this as a challenge or an opportunity, but homicide cases and violent crime overall in the city has declined over the past 30 years significantly. They currently remain at historic lows. However, the perception of crime in the media and in politics is that it is increasingly dangerous, even though that’s not true in the moment. There are some communities where violence persists, and it’s bad as it ever was. But overall, in the city, it’s gone down despite the perception that it’s worse. Does that present a challenge to you with people thinking like, “Well, crime is terrible out there. This is not going to work.” Or is that an opportunity where you can say, “Well, let’s unpack these numbers. Crime is actually at a historic low.

I really appreciate the way you framed the crime statistics. That is the way I understand it. … Crime data is notoriously difficult to decipher, but that is the way I understand the crime problem, that it is at historic lows, even though it did spike post-pandemic and that there is a perception right now of increased violence. So, I first of all agree with you on the framing, which is not always the case for me. So, there’s a win, number one.

OK, I’ll take it.

So, what do we think about the perception of unsafety? I think it’s serious. It matters to people. I think I feel more on edge, and I think when we are more on edge, we can pop more. We can lash out more. So, there’s something there to it, even if we don’t see the statistics in that way. What do statistics really mean? What you want is to feel safe. And so, I just want to validate that, that that’s really important. And in the communities where crime has been persistently high, we talk about these historic lows, but as you said, there are places where that’s a joke. That feeling of unsafety is real for people and needs to be acknowledged and validated and dealt with in a real way.

I see the work that I’m doing, it is not scaled. It’s not like we’re doing this in every moment in every place. I guess I’ll say I can’t really answer your question. I would say that I’m just trying to show, and many people who are doing this work in this city and there’s a lot of amazing people doing this work in all corners and in all different ways and in their communities, we’re doing something different. We’re not necessarily attacking the crime problem. We’re trying to replace the legal system so that we can be apples for apples. We’re trying to show that connection matters, that our sense of safety is increase when we feel connected to the people around us. These are the things that we’re trying to do that you can move forward. That you can move forward if you’re supported and if you’re resourced to. If we can invest in helping people move forward, they will be able to move forward.

Really, we’re trying to show that a different way is possible to get the crime reduced and to get this feeling of unsafety reduced and to get real crime in our specific neighborhoods who have it to have their crime actually reduced is going to require a lot of different things. It’s going to require investment in the things that really make us safe, which is ending poverty, increasing housing and resourcing people so that they have really good schools and opportunities. Those are the things that are going to hit that issue in a real way. And I think that the work in restorative justice, part of it is narrative work to say, “Hey, this is why we are all connected and your unsafety impacts me and how do we all move forward together?” And it’s not apples to apples. Here’s how you replace the criminal justice system that has failed so many people.

Does that [crime data] not suggest that the legal system is doing its job as it is?

It’s not that I haven’t thought about that. I’ve thought about that. I think in moments it has possibly incapacitated people who were going to cause more violence, but I think what we’re seeing in our jails, and if you spend any time up close and personal with what’s happening in the jails, it is causing violence. I don’t see how you can meaningfully look at the conditions on Rikers Island, which is a real blight on our city. You can’t really look that in the face and say, “Well, the rest of our city is safer. And so, therefore, it’s OK that you live like this.” Even if that were to be the case, which I don’t actually think is true, and I think the violence in Rikers Island then gets replicated out on the street. So, I actually don’t think it keeps us any safer. But I don’t think you can look at it and say, “This can keep going the way it is.” One of the biggest challenges for me is I have worked with people who are incarcerated, and we create this beautiful connection, and they tell me stories of what’s going on inside. I just feel like I’m going to pull my hair out. I can’t believe that we allow this to continue. We certainly have evidence that is not contributing to safety.

Where in Brooklyn are you based? What’s a day off? You don’t have any justice to restore.

I put my cape down. I live in Kensington. I love my neighborhood. I love Brooklyn. I think the pandemic was a turning point for me in a way where I was just like, “OK, that’s it.” Even though I love Montreal, I’m throwing down for Brooklyn and the way people show up for each other in the mutual aid that was happening. This place is amazing and Kensington itself is so diverse. I’m a mom of three. I have a stepson and then two more. And so, it’s pretty rowdy in my house. And there’s a lot of food to be made all the time, and the kids are just always hungry.

It doesn’t stop. I just find I’m doing dishes all the time.

It’s a lot. After I won the David Prize, I was like, “I won the David Prize. I’m going to go do the dishes.” You don’t skip a beat. But. I like my coffee. Anyone who knows me listening to this and is saying like, “Erika, just admit that you want to go get a cortado.”

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like