From left: Andy Curtin and Aaron Lefkove (All photos courtesy Aaron Lefkove)

The setting of the sun is a difficult time for all fish: The rise and fall of Littleneck

The Brooklyn restaurant group I co-founded in 2011 is serving its last dishes. Here’s how it all went down

The seed for Littleneck germinated sometime in early summer 2010 and entered this world after no small amount of labor pains on October 26, 2011. It was a collaboration between myself and a business partner, Andy Curtin, who’d I’d ride it all out with. I thought of the name while we were doing a tequila shot at Clem’s, miraculously remembered it the next day, and once we had that, everything else came easy — which makes you wonder what other ideas in bars should have been followed up on.

On paper the idea was insane. With minimal restaurant experience — a combined resume of server, dishwasher, pizza delivery driver and a brief stint at a Wendy’s — setting up a clam shack steps away from America’s most polluted waterway may have seemed, to put it mildly, novel at the time. We were not grizzled industry veterans or a large hospitality group with any significant financial backing. We never had the luxury of cutting our teeth on someone else’s dime. And if there’s a restaurant cool kids table we were never offered a seat. Many times during Littleneck’s buildout, and then again after it opened, I wondered if we were visionaries or morons. I still don’t have clarity on that. But the New York hospitality ecosystem is built on the backs of cockroaches both literal and figurative. Our 13-year run spread out over four restaurants, a makeshift music venue and countless pop ups — all thanks to us being cockroaches. We were too tough to die until we weren’t. But everything dies, baby, that’s a fact, and as of this writing it’s all dead.

‘We built the place ourselves’

Sledgehammer time!

We built the original iteration of Littleneck ourselves. And by that I mean we actually, literally built the place ourselves. As in, we came in with sledgehammers and tore down what was already inside, ripped up the soggy carpeting and parquet and refurbished the existing 100-year-old hardwood floors; trenched out the concrete in what would become the kitchen and laid a new waste line; plastered the crumbling walls; applied enough coats of polyurethane to keep us high well into the next decade. I mean, we built the place ourselves.

I’ll back up for a second. When we first found the space where the original Littleneck sat it was a decrepit storefront a few doors down from one of the last remaining social clubs in Gowanus. The previous tenant sold chess sets and manufactured trophies on the side. By the time we got to it, the roof (or what was left of it) had to be replaced. We ripped that off, including the landlord’s deck, which sat on top and was precariously close to crashing through the rotten ceiling joists. We replaced those too. By the time we sold the place in early 2020 the deck remained unfinished. There was minimal gas, plumbing and electrical service. If you are thinking of opening up a restaurant of your own please leave those jobs to professional tradesmen — trust me on this one. Somehow it all got done, though.

Enter Alan Harding — a down-on-his-luck journeyman chef who showed up to our job site with a paper copy of a resume that listed the restaurants he’d opened on Smith Street (they were numerous) and that he was once an in-house chef at MTV. It might’ve glossed over his time spent under a fledgling Thomas Keller at Rakel. Personally, I would have led with that.

By 2011 Alan was, by his own admission “box office poison” (his words, not mine). Andy and I provided the space and whatever cash we could scrape together. Alan provided a basic opening menu fashioned around our loose criteria of what a New England style clam shack should be, as well as an antique punchbowl allegedly a wedding gift from his ex-father in law, the photographer Gordon Parks. For the next nine years we used it to keep our by-the-glass selections chilled. It’s the only thing I regret leaving behind when we eventually sold the place.

Alan understood the assignment. Maybe too well — the three subsequent kitchen managers under our tenure as well as the next owners more or less adhered to his original vision with only minor tweaks. As of this writing his mussels, steamers, fisherman’s stew, chowder and takes on the lobster and full belly clam rolls remained on the menu until the end. Andy and I never made him a partner — and in fact we later fired him unceremoniously — but the place was always partly his even long after we parted ways.

Littleneck was a success out of the gate, much to the chagrin of its detractors, and ups and downs aside, it remained so for the next seven or eight years.

A year in and high on our own success we partnered with Alan and his friend who was a local handyman to take over a former bagel shop two doors down and open The Pines. The details of our involvement in that restaurant are inconsequential to this story except to say that by the time the first Friday night service rolled around, we were all sitting across from each other in a downtown Brooklyn courtroom and the eventual settlement paid for our next venture, Littleneck Outpost in Greenpoint. It should however be stated that the pasta in that restaurant was sublime.

The cash-only Gowanus restaurant might’ve been used like an ATM to finance our growth, but Greenpoint — the longest running and most lucrative and successful of any of our ventures — was always the most viable location.

In 2013 we signed the lease on a space on Franklin Street in Greenpoint that had been vacant since 1980 and got what I still believe was the last great real estate deal in town. For 33 years, the landlords — a retired teacher in Connecticut and her brother, a local drunk who lived in a house around the corner — used it as a clubhouse. When we first set foot in the place it was filled floor-to-ceiling with junk: disassembled slot machines, disassembled radios, various electronic projects, a toilet connected to no form of plumbing below save for a 33-year-old puddle of piss. It’s miraculous a place like that could’ve existed in such disarray in a prime locale for three decades and honestly it was a slice of eccentricity that has long since been pushed out of New York. (Don’t worry, I have enough self awareness to know in this case I am partially to blame.)

The neighborhood exploded with growth as soon as we opened. If Gowanus’ timing and locale was dumb luck, then lightning struck a second time when Outpost arrived.

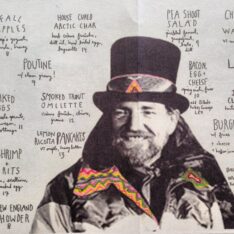

Le menu

A Williamsburg Bridge too far

It’s easy to look back now and see when the cracks started to show and taking the concept to Williamsburg for our third restaurant Littleneck Grand proved to be a bridge too far.

131 Grand Street had a long affiliation with the freak scene that was once prevalent in Williamsburg. It’s hard to believe there was once a free store run by anarchists on the corner of Grand and Berry. And after that there was Passout Records — a record store in name only — run by a legend who still haunts the East Village, Pee Wee Masco. If you wanna talk about New York’s hottest club, for a time it was Passout. This place had it all: regular Saturday matinee punk shows held in the shop on a day she knew the Hassidic landlord couldn’t be reached via phone; hourly rehearsal studios in the basement; junkies living in a room under the stairs shooting dope and freebasing coke; an art gallery that actually showed some really decent stuff (I still regret that they were too fucked up to figure out how to sell me a couple pieces from the Mike Diana show but that’s neither here nor there).

For a time the place ran like a well oiled squat. At some point Pee Wee had the bright idea to turn it into a burger version of San Loco, and when the 24-hour restaurant in the former record shop squat didn’t pan out we entered the picture.

Littleneck Grand was the first domino to fall and possibly one of the more expensive lessons in the sunk-cost fallacy. The place should have never existed — something Williamsburg diners, or the lack thereof, reminded us of on a daily basis. It would’ve been much more enjoyable had we just piled all that money in the middle of the street and lit it on fire. And honestly with the 10-year affiliation I had with the space under its previous incarnations I really should’ve known better. But greed is often a more powerful motivator than fear. The ways in which the curse of Passout haunted this money pit unmitigated shitshow could fill volumes, but I will leave you with the following anecdote.

If you don’t know what a Robot Coupe is, it’s a supercharged French food processor from the same people who brought you the guillotine and it’s just as effective at severing whatever limbs have the misfortune of passing through. I once scooped a prep cook’s fingers out from under the ice machine where the Robot Coupe had spit them, threw them in a quart container with some ice from the same machine I found them under — the fingers were no longer attached to the hand at this point if that wasn’t already clear — and off we went in a yellow cab to Bellevue to see if they could be sewn back on (they could). Some calamity like that seemed to befall that restaurant every day. That’s how fucked the place was.

We were no longer in the Williamsburg of Todd P’s heavily punctuated email blasts — or of Monster Island, or Sweetwater when it was still a bar with Discharge on the jukebox, and what’s now referred to as indie sleaze although I only heard that term for the first time last year. For added context I urge you to checkout Fletcher C. Johnson’s essential “Complete History of Williamsburg” for a full retelling of that era. We’d entered into the Williamsburg of clout-chasing food-world influencers — though it’s debatable who if anyone is actually being influenced by their grift—and the late capitalist dystopian hellscape of high rise waterfront condominiums efficiently pumping out mountains of Mint X trash bags and piles of disassembled Ikea furniture. Our earnest attempts were as anachronistic as the bygone venues I just outlined above.

When it was evident that the concept had fallen in deaf ears and it was time to pull the plug I was persuaded to give it one more quarter that ultimately sent us into an additional $76,000 of debt. We finally finished paying it down in the summer of 2022.

A couple months after we closed, we rented the space out as a location in Martin Scorsese’s “The Irishman” and got to watch the place get blown up onscreen. Small consolation, but consolation nonetheless.

We can discover the Wonders of Nature

If there’s any silver lining here it’s that we teamed up with Andy Bodor the erstwhile proprietor of Cake Shop and ran the space as Wonders of Nature, a DIY avant garde venue, until the landlord would let us off the lease. It was a chance to give something back to the musical community both Andys and I were a part of, and the booking was on point. Hamish Kilgour of The Clean played a solo set; Lydia Lunch would hang out at the bar; Garcia Peoples did a month-long residency. It was perfection.

But, the place was yet again a money suck helped along by our cash only Gowanus restaurant and when we finally came to terms with the landlord to exit the lease at the two year mark it could not have been more of a relief. That said, Wonders of Nature was the most nihilistic venture I’ve ever been a part of and it was also the most enjoyable.

The final night of Wonders of Nature was a solo acoustic set by Evan Dando of the Lemonheads. He played every song off of “It’s a Shame About Ray”.

I walked back home to my place after the gig, fell asleep and as far as I can recollect had a nightmare around 4 a.m. that I got a call from the landlord in Connecticut that the building was on fire. “Damn I must be buggin’ out.” I thought until I looked at the phone again, realized it was in fact not a dream, and sprinted the 20 blocks from my apartment on McGolrick Park to Franklin Street just in time to catch the FDNY and NYPD who had kicked our doors down. There had been a small fire in the backyard where someone had piled a bunch of scrap wood and aerosols.

“Oh good you’re here,” a cop said. “We were about to come over to Russell Street to get you out of bed.” Real estate in New York City — especially in its more neighborhoody enclaves like Greenpoint — can be a relationship game. My Russell Street landlords were like if you could imagine Patty and Selma from the Simpsons living in Grey Gardens. A 4 a.m. wakeup call from the cops on a month-to-month lease should’ve spelled certain disaster.

It was September 30, 2018 and it was the day the initial term of the Outpost lease was set to expire. Because as we approached the renewal option period on the lease for Outpost the landlord had unilaterally decided not to grant it and a legal arms escalation ensued until they finally relented.

If there’s one lesson to take from the restaurant business it’s that you can skimp on everything else but always pay for top-shelf legal representation no matter the cost because otherwise life’ll kill ya! And it was the day the landlord’s who we’d been beefing with us over picking up the five-year option wanted us gone. “I guess the landlord lived on the block but he died earlier this week,” the cop told me. “He’s dead?!” was my only thought. A landlord’s final fuck you from beyond the grave in the form of a trash fire.

Another Grand mistake

Somewhere amidst all this we got a call from one of our former employees who had more or less taken our Greenpoint concept (and a couple of our former employees) to a space near Grand Street and Bushwick Ave., renamed it with our dishes and all, tried to run it himself, and within a few days of opening was run out of town — this was in a time before they had a word for it: “canceled” — for being a charter member of The Proud Boys, the racist incel club deputized by a guy from Vice magazine in the backroom of a bar on Manhattan Avenue and later deployed with great effect by a tacky midtown realtor to lay siege to our nation’s capital. He had a fully built-out space he planned not to return to and would we like to take over the lease? Once again greed outweighing fear … or honestly at that point just common sense. We took the space and gave Williamsburg one more try.

There’s no feeling in the pit of your stomach quite like the feeling in the pit of your stomach when the audit letter arrives from New York State. Before you even open the envelope you know exactly what it is because it doesn’t look like any correspondence you’ve received before — and at this stage in the game you’ve received a lot from the tax man. The feeling is only compounded when you receive two in the same day. Being on the business end of one of the more efficient and well-funded government agencies in the country ain’t fun but in this instance it was a saving grace.

The viciousness of the inspectors from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the DOH for short, also can not be understated. They are the angriest and most foul people you’ll ever do business with and in a city where money talks they have the ability to deploy arcane codes that will make or break even the mightiest of operators all on a whim and a civil servant’s salary. While most of the city got to sit home and watch the hospitality industry incinerate in real time during the Covid lockdown, there were at least a few operators out there who felt no small amount of schadenfreude watching the agency first neutered in the lawless early days and then gutted during the social upheaval and “labor shortages” of peak pandemic. It was a bright spot of an otherwise particularly bleak era.

I tell you all of this because in late 2019 Littleneck Outpost received the dreaded yellow sticker when it was shut down over mouse droppings in the basement among other lesser infractions.

Mice are a reality in New York and when you’re working in hundred-plus-year-old buildings, no matter what you do, you can’t totally build them out — and I spent over a decade trying. You can only mitigate the problem.

The November 2019 closure — the second DOH closure in as many years for a problem that could never properly be remedied and didn’t seem to be going away unless the landlords pitched in on their side of the basement — coupled with the final bill from the taxman’s audit and a nine-year-old seafood restaurant whose expenses were rapidly beginning to eclipse its revenues was a breaking point. We had no idea that a once-in-a-century pandemic was coming down the pike just a few months later. We just knew it was a tight spot to be caught up in.

On a cold December afternoon in 2019 in that liminal week between Christmas and New Years I walked into to the Williamsburg Cinema for a weekday matinee of “Uncut Gems,” the Safdie Brothers’ Adam Sandler vehicle about a diamond district hustler’s attempts to stay one step ahead of creditors, loan sharks, and a web of problems of his own making. I walked out of the theater thinking I had just watched a documentary.

Lefkove with Erin ‘Sniff’ Norris, an early employee (and current proprietor of OurHaus)

86 Littleneck

I was sipping a pastis in a seafood restaurant in Provence in January of 2020 when I got the call: The landlord on Third Avenue would go along with the reassignment. The culmination of the chain of events in November sparked the idea that maybe we should sell the original location. Most operators might’ve closed up shop given our circumstances. It’s possible we acted out of a sense of loyalty to our employees who seemed to still love working at the place despite its best earning years being well in the rearview by 2020. Who were we to deny them of that? Or maybe we knew that New York State would put a levy on the sale guaranteeing us a full payout with no buyer default on the deal which we held paper on for 18 months.

At any rate, we couldn’t have found better stewards to keep our dream alive than the couple that worked as bartenders and would eventually step up and guide the restaurant through a turbulent four years from 2020 until its recent demise. I can’t comment on the pandemic era down there, but I imagine it couldn’t have been easy, so respect for making it out of the hard times. The recent news they were planning on closing the original Littleneck came as both sad but also not a total surprise.

The pandemic was not kind to restaurants in general nor was the rising cost of food, the wildly inflated costs of utilities and insurance, and the unpredictable habits of a population collectively shook. Andy and I soldiered on through the pandemic with Littleneck Outpost and the East Williamsburg offshoot with the newer location trying its hand as a prep kitchen, bakery, catering kitchen and ultimately storage space. At one point we even had another group lined up to take over the lease who went as far as giving us a deposit before getting in a fight and punching each other in the face and ultimately scattering from New York completely.

Finally the East Williamsburg location succumbed to Covid-related complications — a lack of viable revenue — and quietly passed on. Greenpoint made it to the end of the 10 year lease, but in the process the building changed hands. By the end Outpost was busier than it had ever been and was somehow still losing a couple grand a week even running with skeleton crew and skeleton menu. The new corporate management company graciously offered a 60 percent rent hike which wasn’t the cure-all I’d hoped for and Littleneck Outpost left this world in late 2023.

The pandemic and its long tail effect was a mass extinction event for restaurants no matter your knife skills or how you slice it. Those that survived learned to navigate a new and truly hellacious landscape.

The restaurant world — like the guests who fill them up every service, like the people who operate them, like the neighborhoods that make up the town — is constantly rewriting itself with a new cast every season. A decade ago I was named by this very publication (which itself has since changed hands) as one of the borough’s most influential food world figures. A glance at this list now and one can see how much the business has written and rewritten itself over and over.

Restaurants are New York’s great equalizer. There is no other industry where people from every socioeconomic strata play side-by-side as equals — if you can throw down in the kitchen or on the floor you can play ball. The diversity that exists in hospitality — at least in the rank and file — exists in no other business. Not advertising, not Wall Street, not media, not fashion, not tech, not any of the city’s other glamor industries. I’ve seen shifts where PhD candidates work alongside guys that 48 hours prior were in a safehouse and 48 hours prior to that were running across the southern border. Each of those people play an equally crucial role because when you’re in the shit there’s no one that’s gonna tell you one job is any more important than another. Everyone’s gotta work in harmony or the whole thing crashes down. It is often people’s first stop on the way to a new life and new opportunities as well as people’s last stop before departing to the next stage — post-graduate, parenthood, fame, fortune, a bar or restaurant of their own…you name it. And for some people it’s their everything. It’s a place where people who exist in the margins of society can get a leg up in the world.

For the guest as well, restaurants play a crucial role. In New York City only the exceptionally wealthy or the exceptionally well trust-funded can entertain at home, so restaurants — the proverbial third space — become our homes. Instead of dinner and a show oftentimes dinner, as they now say, often is the show. In a city as unforgiving as New York, we sell escapism; we sell experiences the way the pornographer’s thin plot lines sell viewers on an attainable reality, something they can feel in on and maybe be a part of even for a fleeting night. And as New Yorkers we have a divine right to eat in the dopest restaurants in the world and to gloat about it with pride because we don’t live in a backwater here.

You might also like